Square Number Surprises

There are unexpected discoveries to be made about square numbers...

Problem

Square Number Surprises printable worksheet

You're probably very familiar with the sequence of Square Numbers: $$1, 4, 9, 16, 25...$$

Below are some ideas to explore with square numbers.

For each one, try a few examples and see what you notice.

- Add two consecutive square numbers and then subtract 1

- Square any odd number, then subtract 1

- Multiply two consecutive odd numbers and then add 1

- Multiply two consecutive even numbers and then add 1

Can you explain what you've noticed?

Can you prove that it will always happen?

Can you come up with any Square Number Surprises of your own?

With thanks to Don Steward, whose ideas formed the basis of this problem.

Getting Started

You might find some of the ideas in Quadratic Patterns and Pair Products helpful.

Student Solutions

Most of you started by calculating some numerical results. Luke and Emily from Woolston Community Primary School and Kieron from Bayside Comprehensive School, Gibraltar started in this way:

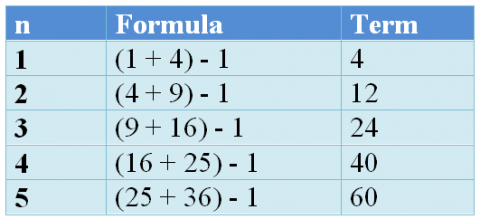

1. If we add two consecutive square numbers and then subtract $1$ we get the first five terms are:

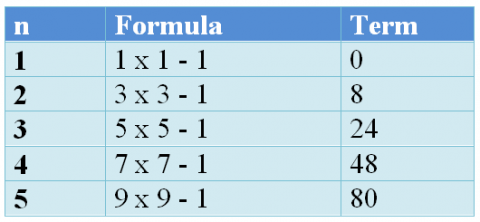

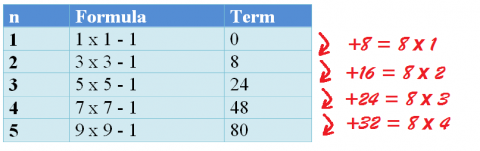

2. If we square any odd number, then subtract $1$, the first five terms are:

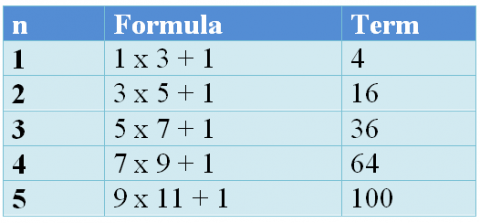

3. If we multiply two consecutive odd numbers and then add $1$, the first five terms are:

4. If we multiply two consecutive even numbers and then add $1$, the first five terms are:

Ankit from Tanglin Trust School, Singapore, and Leo from University of Chicago Lab Schools, USA, then realised that some results are always odd while other are always even:

1. We noticed that the result is always even. This is always true, since, for any two consecutive numbers, one would be even and the other one odd. Since the square of an even number is even and the square of an odd number is odd, one of the squares of the two consecutive numbers will be even, and the other will be odd. Hence their sum will be odd. So, if we subtract one, the result will be even.

Therefore, subtracting $1$ from the sum of two consecutive square numbers will always give an even answer.

2. We notice that the results are even as well. If we square an odd number, the result will be odd. After subtracting $1$ it will be even.

Hence, subtracting $1$ from the square of an odd number will always give an even answer.

3. We observe that the results are all even. If we multiply two consecutive odd numbers, the result will be odd. If we then add $1$ the result becomes even.

Hence, the product of any two consecutive odd numbers plus $1$ is always even.

4. We observe that the results are all odd. This always happens since, if we multiply two consecutive even numbers the result will be even. After adding $1$ the result becomes odd.

Hence, the product of two consecutive even numbers plus $1$ will always give an odd number.

Irene, from the King's College of Alicante, Spain, was able to express some general findings:

1. When you add two consecutive squares and then subtract one you get twice the first of the squares plus its root. ($m^2+(m+1)^2-1=2(m^2+m)$)

2. When you square any odd number and then take away 1 you get the product of the even numbers next to it ($(2m+1)^2-1=2m(2m+2))$).

3. If you multiply the even numbers next to $m$, which is odd, and add one you get $m^2$.

4. If you multiply the odd numbers next to $m$, which is even, and add one you get $m^2$.

Dani from the British School of Alicante, Spain, Julian from the British School, Manila, Philippines, and Jacob from Netherhall School were able to explain some of these patterns:

1. Two consecutive numbers can be denoted by $n$ and $n+1$, therefore, two consecutive square numbers are $n^2$ and $(n+1)^2$. If we subtract $1$ from their sum we get: $n^2 + (n+1)^2 -1 = n^2 + n^2 + 2n+1 -1 = 2n^2 + 2n = 2n(n+1)$.

One of the two consecutive numbers $n$ and $n+1$ should be even, so $n(n+1)$ is even, which implies $2n(n+1)$ is a multiple of $4$.

2. An odd number can be denoted by $2n+1$ (since $2n$ is even for any value of $n$ and then by adding $1$ we get an odd number). Therefore, an odd number squared minus $1$ can be represented by $(2n+1)^2 - 1 = 4n^2 + 4n +1 -1 = 4n(n+1)$.

Similarly as before, one of the two consecutive numbers $n$ and $n+1$ is even, so $n(n+1)$ is even, which implies $4n(n+1)$ is a multiple of $8$. (And hence, a multiple of $2$ and $4$).

3. Two consecutive odd numbers can be denoted by $2n-1$ and $2n + 1$, so the product of two consecutive odd numbers plus one is $(2n-1)(2n+1) +1 = 4n^2 -1 +1 = (2n)^2$.

Therefore, the number is always a multiple of $4$ and a square of an even number.

4. Two consecutive even numbers can be denoted by $2n$ and $2n+2$. So the product of two consecutive even numbers plus one is $2n(2n+2) + 1 = 4n^2 + 4n +1 = (2n+1)^2$.

Hence the result is always the square of an odd number.

Tim, from Gosforth Academy, UK, realised that the second, third and fourth parts are all based on the same result:

We know (by multiplying the brackets) that $(x-1)(x+1) = x^2 -1$, for any value of $x$.

The seond part uses the result starting from the right hand side, for $x$ being odd (i.e. $x = 2n+1$ for some $n$). Then, $(2n+1)^2 -1 = 2n(2n+2)$.

The next two parts use a slight variation of the mentioned result: $(x-1)(x+1)+1 = x^2$.

For the third part we take $x$ even (i.e. $x = 2n$), and so we get $(2n-1)(2n+1) +1 = (2n)^2$, a square of an even number.

For the last part, we take $x$ odd (i.e $x = 2n+1$), and so we get $2n(2n+2) + 1 = (2n+1)^2$, a square of an odd number.

Abigail from England, Timothy from King's School Macclesfield, England, and Dani from British School of Alicante, Spain, noticed something interesting about the differences of two consecutive terms in each sequence:

1. For the first sequence, if we compute the difference of the neighbouring terms, we will get consecutive multiples of $4$:

2. For the second one, if we again compute the difference of the neighbouring terms, we get consecutive multiples of $8$:

3. For the third part, we take again the difference of neighbouring terms, and do the same thing with the resulting sequence. We then notice that we only get $8$:

4. Doing the same procedure as for the third part, we notice that we once again get only $8$ for the last sequence of differences:

Varun and Sean from Tanglin Trust School, Singapore, noticed a link between the first two results and triangular nubmers:

1. We noticed that if we divide the numbers in the sequence by their highest common factor ($4$) we get triangular numbers: Dividing $4, 12, 24, 40, 60, ...$ by $4$ gives $1, 3, 6, 10, 15, ...$.

2. We do a similar thing as above. This time, the highest common factor of the sequence is $8$, so we divide each term of the sequence $0, 8, 24, 48, 80, ...$ by $8$, and we get $0, 1, 3, 6, 10, ...$, so triangular numbers as well.

There is also a geometric interpretation for this problem:

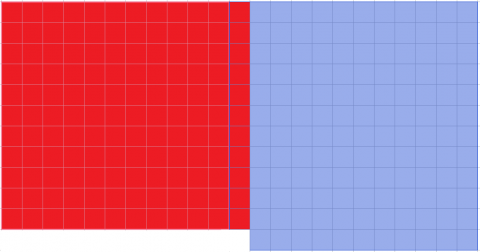

1. We construct two consecutive squares one with side of length $n$ the other one with side of length $n+1$:

We now take out one square:

We now have two identical rectangles, as in the figure below:

2. Now consider squaring any odd number $2n+1$ and then subtract one. Since the number is odd, we will have a middle square. We will subtract that one.

Now we recolour the squares so that we get four identical rectangles as below:

The four rectangles have sides of consecutive lengths, so their area is even. Since there are four of them, the area of the figure is divisible by 8.

You could also see this as two copies of the shape given in part 1 rotated and put together.

3. We now have a $n$ by $n+2$ rectangle, where $n$ is odd to which we want to add a unit square, as below:

Now we move the red line of squares from below and the unit square so that we get a larger square:

The new square has the side with one unit bigger then the shortest side of the rectangle. Since the side of the rectangle was odd, the side of the square is even.

Therefore, we have constructed an even square from the given rectangle and the unit square.

4. Similarly as before, if the side of the rectangle was even, wen whe moved the red side we created a square of side one bigger then the lower side of the original rectangle. This time, since the rectangle has even side, the side of the square will be odd.

For the first two parts, we could use triangular numbers to visualise the pattern:

2. For the second one, we recolour it like this:

We have now $8$ identical triangular numbers, so the area of the shape is a multiple of $8$.

Timothy, from the King's School, Macclesfield, created some Square Number surprises of his own:

If you have $4$ consecutive square numbers, say $9,16,25,36$ then add up the 1st and 4th numbers and subtract from it the sum of the 2nd and 3rd numbers. What do you notice?

If you add up two square numbers that are apart by one e.g $1$ and $9$, $4$ and $16$, then find the sum of the $2$ numbers, what do you notice?

Irene, from King's College of Alicante, Spain, also created a Square Number surprise of her own:

Take any set of 5 consecutive numbers. Then if you add 4 to the product of the two extreme numbers in the set you get the square of the number in the middle.

In order to prove that, I denoted my 5 consecutive numbers by $n, n+1, n+2, n+3$ and $n+4$. If we multiply the extremes and add $4$ we get: $n(n+4) +4 = n^2 + 4n+4 = (2n+2)^2$, which is the square of the middle number.

Usman, from Twyford Cofe High School, UK, thought at something else:

When you multiply two consecutive odd numbers and then subtract one, the result is two less than the square of the even number between.

I started by computing the first few terms in order to observe the pattern. Then I chose $2n$ to describe my even number. The two odd numers on its sides will then be $2n-1$ and $2n+1$. If we multiply them and subtract $1$ we get: $(2n-1)(2n+1) - 1 = (2n)^2 -2$, which is two less than the square of the even number between.

Well done to everyone who sent in a solution!

Teachers' Resources

Why do this problem?

This problem offers students an opportunity to explore particular numerical cases which give rise to patterns that they may be keen to explain. When they are ready, students can make generalisations, and appreciate the power of algebra to capture the generality in a concise and elegant way.

Possible approach

This printable worksheet may be useful: Square Number Surprises.

You may wish to split the class into groups and give one of the four challenges to each group. Alternatively, you could introduce the first challenge and work through it as a whole class, and then set students the remaining three challenges to try.

Encourage students to start with lots of numerical examples first, and then to write down everything they notice about their answers. Then share ideas for how to explain what they have noticed. If nobody suggests doing so, draw attention to the idea of using $n$ to represent a general number, and encourage students to write expressions for the general term for each of the four challenges.

The first two challenges lead to an expression which includes the term $n(n+1)$ so there's a good opportunity to discuss how we know that $n(n+1)$ must always be even. Students may make the connection with the formula for the triangular numbers $\frac{n(n+1)}{2}$, which always gives a whole number.

The second pair of challenges could lead to the expansion of $(n-1)(n+1)$ to give $n^2-1$ so this could link to work on the difference of two squares - see Hollow Squares and What's Possible?.

Key questions

Which numbers might it be a good idea to start with?

When we try some larger numbers, do the patterns we've noticed still hold?

How could we prove that the patterns will continue?

Possible support

Quadratic Patterns offers an exploration of quadratic number patterns using multiple representations, so might be a good task to ease students into this sort of generalisation.

Pair Products offers an accessible and scaffolded context for exploring expansion of double brackets.

Possible extension

Students might want to try Always Perfect and Perfectly Square next.