The Problem-Solving Classroom

This article forms part of our Problem-solving Classroom Feature, exploring how to create a space in which mathematical problem solving can flourish. At NRICH, we believe that there are four main aspects to consider:

- Highlighting key problem-solving skills

- Examining the teacher's role

- Encouraging a productive disposition

- Developing independent learners.

This article will address each of these in turn, drawing attention to appropriate NRICH tasks along the way.

Part 1: Highlighting Key Problem-solving Skills

One of the ways we can help learners become better problem solvers is by repeatedly and explicitly giving them opportunities to develop key problem-solving skills. NRICH defines 'problem-solving skills' as those skills which children use once they have got going on a task and are working on the challenge itself. The skills which we consider to be key at NRICH are:

- Visualising

- Working backwards

- Reasoning logically

- Conjecturing

- Working systematically

- Looking for patterns

- Trial and improvement.

Zios and Zepts takes learners to the planet of Vuv, where there are two types of creatures - Zios (which have three legs) and Zepts (which have five legs). The activity offers a context in which to discuss trial and improvement and working systematically, and the way that these two skills are often used together. Once we have one solution (perhaps by trial and improvement), how many other possible answers are there and how do we know we have got them all (systematic working)?

Finding a winning strategy for the game Got It lends itself to a working backwards approach. After playing a few times, pupils will be able to spot which player is going to win before the winning move takes place. From this point, pupils can work backwards to find the winning approach.

How Would We Count? involves discussing how many dots pupils can see, and the strategy they use to count them. This encourages learners to discuss how they are visualising the number patterns within the dots, and helps them appreciate that there is no 'right' way to go about this task.

Play to 37 is a number game for two players, in which the winner is the player who hits the target of 37 exactly. Asking children to consider the number of numbers it takes to make the total in each game and inviting them to comment on what they notice, will help them towards a generalisation so they can apply their strategy to other, similar games (e.g. when the total is changed).

Snake Coils is a truly 'non-routine' problem which we suggest you have a go at yourself and then reflect on the problem-solving skills you used. How could you encourage the pupils in your class to have these skills at their fingertips?

For further support on the development of key problem-solving skills, see our Problem-Solving Feature, which includes several articles and links to more activities which will give learners experience of specific problem-solving skills.

Part 2: The Teacher's Role

It is perhaps easy to underestimate the effect teacher behaviour can have on enabling problem solving in the classroom. Ruthven (1989) describes a three-pronged approach to teaching and learning mathematics (Exploration, Codification, Consolidation) which contrasts with the more 'traditional' model of demonstration then practice. To illustrate this, let's take a look at a sequence of two NRICH tasks:

The Domino Sets investigation challenges learners to work out how they would check that a box of 0-6 dominoes they are given is a full set. This encourages them to explore the structure of the dominoes in their own way. You can ask them to arrange the dominoes on the table to show you that they have/have not got a full set and then all children can have an opportunity to look at others' arrangements. By inviting the learners themselves to justify their answers, you can draw out the key features of the dominoes and the systematic approach that is required. This is the codification stage, where you are highlighting key learning points and perhaps introducing specific vocabulary. Consolidation of the ideas comes in the form of another task,

Amy's Dominoes, which also involves finding out whether a domino set is a complete one, but this time the information focuses on the number of dots. This problem will deepen children's understanding of the structure of dominoes and gives them further opportunities to work systematically and reason logically.

Problems which require estimation and the ability to state assumptions (such as 'how much will you drink in your lifetime?' and 'how many jelly babies would fill the school hall?') can also be a useful vehicle for 'holding back' in the mathematics classroom and giving children the opportunity to explore a situation freely. (This type of task is sometimes known as a Fermi problem.) After you have posed the task, give time for children to talk to each other. You could then invite them to share some questions that have occurred to them as they have been talking. This could lead on to a discussion about the assumptions they will need to make and then you can allow time for pairs/small groups to come to a conclusion.

If the teacher's role is more of a 'guide on the side' rather than a 'sage on the stage', then asking probing questions is of key importance. In her article Developing a Classroom Culture That Supports a Problem-solving Approach, Jennie Pennant draws attention to questioning and groups questions into three different categories:

- stage of the lesson

- level of thinking

- mathematical skill.

However, the way in which we handle answers also requires some attention, which Jennie discusses in the above article too. In particular, research carried out by Mary Budd Rowe (1986) demonstrated that increasing wait time (in this case, pausing after asking a question and pausing after a student response) from 0.9 to 3+ seconds had the following effects:

- The length of student response increases (300-700%)

- More responses are supported by logical argument.

- An increased number of speculative responses.

- The number of questions asked by students increases.

- Student - student exchanges increase (volleyball).

- Failures to respond decrease.

- 'Disciplinary moves' decrease.

- The variety of students participating increases. As does the number of unsolicited, but appropriate contributions.

- Student confidence increases.

If you are interested in reading more about the role the teacher plays in creating a place where problem solving can thrive, then Jennie's article would be a very good starting point.

The following quote (attributed in part to Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and in part to Haim G. Ginott) may serve as food for thought:

Part 3: Encouraging a Productive Disposition

Kilpatrick, Stafford and Findell (2001) outine five essential aspects for developing young mathematicians:

- conceptual understanding

- procedural fluency

- strategic competence

- adaptive reasoning

- productive disposition

and they offer an image of five interwoven strands of rope to reflect the equal importance and related nature of the five aspects. (For more detail see our Mastering Mathematics and Problem Solving article.) Here we focus on 'productive disposition' as this is often given the least attention of the five.

At NRICH, we believe that children learn best when they are curious, thoughtful, determined and collaborative and so we have gathered together tasks in each of these categories on our Developing Mathematical Habits of Mind page. The following tasks are some examples from each category to help you get a flavour of each one.

In If the World Were a Village a range of different types of data are shown displayed in different ways. This encourages pupils to explore which format of representing data is the clearest in each scenario. They are then challenged to choose a set of data and present it for themselves in as effective a way as possible. Tasks such as this one are excellent for developing pupils' curiosity, as the data described is real and links to children's own experiences. There are similar books which can provide starting points for discussions.

In The Remainders Game the computer thinks of a number between 1 and 100 and you have to work out what the number is. In order to do so, you choose a divisor for the number and the computer gives you the remainder. This game is excellent for developing thoughtfulness, as there are rewards for winning in as few guesses as possible but penalties for incorrect guesses or unnecessary questions. This encourages learners to think carefully before choosing each divisor and before guessing the number.

The problem Wallpaper presents learners with images of some pieces of wallpaper and asks that they be arranged in order of size, smallest first. Thoughtfulness is needed in being able to justify why pupils chose the order they did, and the task can lead to an in-depth discussion of what 'size' means.

Stringy Quads is an activity for four people involving holding a loop of string, one corner per person, to make a quadrilateral with one line of symmetry. This task encourages collaboration. Working with others to make a shape with a line of symmetry means that pupils have to direct each other to where to hold the corners, and convince each other that the new arrangement indeed has a line of symmetry.

In Thirsty? pictures need to be sorted into order according to the clues given. Each person in the group is given some clue cards and is encouraged to discuss what they think their card means. Working collaboratively helps pupils develop their reasoning skills, making the task more manageable than working on it alone.

In the Factors and Multiples Game players take it in turns to choose a number which is either a factor or multiple of the previous number chosen. Play ends when one player has no options to choose from so that the other player then wins. The collaborative version involves both players working together to choose as many numbers as possible without running out of numbers to choose from. This version requires determination to find the solution.

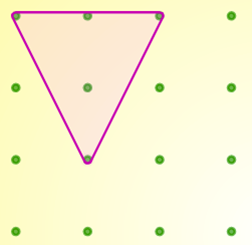

Inside Triangles challenges learners to make triangles on a 4 by 4 grid which have one dot inside them. The task is to work out how many such triangles there are, and to make sure that all possible options have been found. This builds determination by encouraging pupils to persist in order to find all the solutions.

Part 4: Developing Independent Learners

In this section we will explore a range of resources which offer learners the opportunity to develop their independent thinking, all of which have been taken from the Developing Group-working Skills feature. Encouraging learners to become more independent does not equate to them working alone - independence from the teacher can be encouraged in a variety of ways. The collaborative activities below offer such opportunities.

In Number Match every member of the team is given four cards which represent numbers in different ways. The aim is to end up with four cards of a 'set'. This is done by silently (and without non-verbal gestures) passing cards to others in the team. An observer ensures that the rules are followed and notes down which members of the team are actively helping others.

Guess the Dominoes involves working as a team to discover what rule is written on the Ruler's card, using the minimum number of tests. A test involves asking whether a particular domino obeys the rule. This task encourages learners to find out what others think; give reasons for ideas; be concise; reflect on what has been said; and allow everyone to contribute.

In Arranging Cubes the team has to recreate a 2D arrangement of cubes which matches all the information on their cards, without showing each team member's information to anyone else. This challenges learners to listen carefully to each other; ask questions; share knowledge and reasoning; reflect on and make use of what has been said; and come to a consensus.

More tasks which lend themselves to working collaboratively can be found in our Developing Good Team-working Skills article, part of the aforementioned feature.

In conclusion

If we are to create classrooms that allow problem solving to thrive, there are a number of aspects to consider. Encouraging the development of key problem-solving skills should be a priority, along with giving learners opportunities to develop a productive disposition towards mathematics. Taking time to reflect upon our own behaviours as teachers is crucial as this may help us develop more independent learners who relish mathematical challenges.

We hope that you enjoy making your classroom a place in which problem solving can flourish. Do let us know how you get on.

References

Cuoco, A., Goldenberg, E.P. & Mark, J. (1996) 'Habits of Mind: An Organizing Principle for Mathematics Curricula.' Journal of Mathematical Behavior 15 375-402.

Kilpatrick, J. Swafford, J. & Findell, B.(eds.) (2001). Adding it up: Helping children learn mathematics. Mathematics Learning Study Committee: National Research Council.

Rowe, M. B. (1986) 'Wait Time: Slowing Down May Be A Way Of Speeding Up.' Journal of Teacher Education 37 43-50.

Ruthven, K. (1989) 'An Exploratory Approach to Advanced Mathematics.' Educational Studies in Mathematics 20 449-467.

Here is a PDF version of this article.