Sticky Numbers

Can you arrange the numbers 1 to 17 in a row so that each adjacent pair adds up to a square number?

Problem

Sticky Numbers printable sheet (NRICH Roadshow resource)

Look at the following row of numbers:

$$10\quad 15\quad 21\quad 4\quad 5$$

They are arranged so that each pair of adjacent numbers adds up to a square number:

$$10 + 15 = 25$$

$$15 + 21 = 36$$

$$21 + 4 = 25$$

$$4 + 5 = 9$$

Can you arrange the numbers 1 to 17 in a row in the same way, so that each adjacent pair adds up to a square number?

This printable set of cards might help you to test different options.

Can you arrange them in more than one way? If not, can you justify that your solution is unique?

Getting Started

Are there any numbers which can only link to one other number?

Where will you need to place these in your list?

Student Solutions

Well done to James and Joshua from RMH Hospital Schoolroom in the UK, Jose, Veer and Edward from Dulwich College in the UK, Raul and Belen from Cambridge House Community College Valencia in Spain, Laila from England, Amy from Hutchesons’ Grammar in Scotland, Dang Le Anh from Delta Global School in Vietnam, Muhammad Mustafa from Pakistan, Anson, Zahra and Julia from St Mary's College in the UK, Chris from the USA, Rohan from Wilson's School in the UK and Ci Hui Minh Ngoc Ong from Kelvin Grove State College (Brisbane) in Australia who each submitted a solution getting the 17 numbers in the right order, that is:

\[16\quad 9\quad 7\quad 2\quad 14\quad 11\quad 5\quad 4\quad 12\quad 13\quad 3\quad 6\quad 10\quad 15\quad 1\quad 8\quad 17\]

We also received some fantastic explanation. Rohan and Anson started by thinking about the square numbers available. Anson wrote:

Find the ways adding up to every square number until 25 and just put them together without repeating any number.

Other people started by thinking about the numbers available. James and Joshua started with the largest numbers:

[We] worked out that 16 could only be joined to 9 and so had to be at one end. This first attempt came to a dead-end [so we] began to systematically look at other large numbers and how they would need to be paired. [We] found that they all needed to be paired with two particular lower numbers, and used this information to create a chain that worked.

Jack from Concordia Lutheran School in the USA, Chris and Edward also started from the ends. This is Jack's work:

Veer noticed some patterns:

17, 8, 1, 15, 10, 6, 3, 13, 12, 4, 5, 11, 14, 2, 7, 9, 16.

O, E, O, O, E, E, O, O, E, E, O, O, E, E, O, O, E

Key: O-odd E-even

As you can see they all add up to a square number.

The pattern is that they add up like this: 25, 16, 9, 16, 25 and it repeats.

Laila believed there was only one possible chain (which could go in either direction). Can you see how James and Joshua's method adds more evidence to Laila's argument?

This is a unique solution because for the lowest number, 1, there are only two choices, 1 + 8 = 9 or 1 + 15 = 16. We can see that the only option for 17 would be 8 because 17 + 8 = 25. This shows that there is only one order to begin - 17, 8, 1, 15 and this will carry on since each number will only have two other numbers less than 17 that can be added to make a square. One other number, 16, only has 9 that can be added to make a square, so this

must be at the end of the sequence.

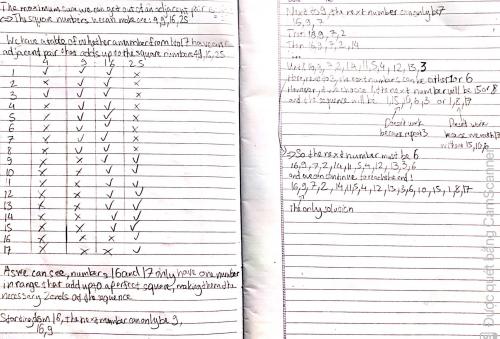

Amy built on this idea to show that the solution really is unique (click on the image to enlarge). Are there any possible connections that Amy missed?

Muhammad Mustafa showed the pairs of numbers on a tree diagram:

I made a tree diagram starting with one and extending it to the number(s) that it can be arranged with. I then did the same with the new number(s) and kept on going until there were no more numbers to choose from. The tree diagram looked a bit like this (this is just a portion of it):

Instead of seeing which other numbers each number should be paired with, Dang Le Anh focused on which square numbers each number could make. This led to the same solution, and a different way of showing that the solution is the only possible solution (click on the image to download the full-size version):

Ci Hui Minh Ngoc Ong used similar ideas to show that there is only one solution, and also found some patterns. Click here to see Ci Hui Minh Ngoc Ong's work on paper, and here to download the spreadsheet that Ci Hui Minh Ngoc Ong created.

Teachers' Resources

Why do this problem?

This problem requires some knowledge of square numbers, but more importantly requires students to think strategically and provide convincing arguments and justifications for their findings

Possible approach

Introduce the problem using the example $10, 15, 21, 4, 5$, explaining that this list of numbers is special because each pair of adjacent numbers add up to make a square number.

Set them the challenge to produce a similar list using all the numbers from $1$ to $17$. Hand out sets of these cards and ask students to work in pairs on this challenge.

After the class have had a few minutes to work on this, add that you would like to know all the possible different ways of making such a list. Challenge them to produce a convincing argument that they have found all the possibilities.

Finally, ask students to present their solutions and justifications to the rest of the class.

An alternative starting point for this lesson could be to ask for 17 volunteers to stand at the front holding one of these cards. With help from the rest of the class, ask them to arrange themselves to satisfy the criteria above. Once they have found a solution, ask them to work in pairs as outlined above to find all the possible arrangements and justify that they have the complete set.

Key questions

Possible support

Students could make a table listing the numbers which can be paired with each of the numbers from $1$ to $17$ to make a square total.

Possible extension

This graph has the numbers from $1$ to $31$ at its vertices. Each edge connects two numbers which add together to make a square number.

Can you use the graph to produce a list of all the numbers from $1$ to $31$ so that pairs of adjacent numbers add up to a square number? Is there more than one way to do it?

Can you find any other numbers $n$ less than $31$ so that all the numbers from $1$ to $n$ can be written in a list in this way? How does the graph help you? Here is a printable version of the graph.