Areas of Parallelograms

Can you find the area of a parallelogram defined by two vectors?

Problem

Areas of Parallelograms printable sheet

b) $\mathbf{p}=\left(\begin{array}{c}3 \\ 2\end{array}\right), \mathbf{q}=\left(\begin{array}{c}0 \\ 4\end{array}\right)$

Choose different vectors $\mathbf{p}$ and $\mathbf{q}$, where one vector is parallel to an axis, and find the areas of the corresponding parallelograms.

Can you discover a quick way of doing this?

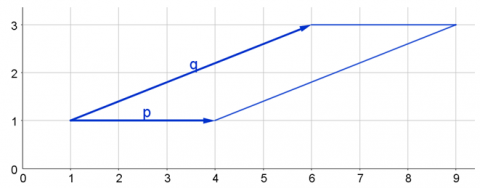

Here are two more parallelograms, again defined by vectors $\mathbf{p}$ and $\mathbf{q}$. This time, neither $\mathbf{p}$ nor $\mathbf{q}$ is parallel to an axis.

Can you find the areas of these parallelograms?

c) $\mathbf{p}=\left(\begin{array}{c}4 \\ 1\end{array}\right), \mathbf{q}=\left(\begin{array}{c}3 \\ 3\end{array}\right)$

d) $\mathbf{p}=\left(\begin{array}{c}2 \\ 4\end{array}\right), \mathbf{q}=\left(\begin{array}{c}-1 \\ 3\end{array}\right)$

Choose some other vectors p and q, where neither p nor q is parallel to an axis.

Can you find a quick way of working out the areas of the corresponding parallelograms?

Can you find the area of the parallelogram defined by the vectors $\mathbf{p}=\left(\begin{array}{c}a \\ b\end{array}\right)$ and $\mathbf{q}=\left(\begin{array}{c}c \\ d\end{array}\right)$?

If you have found a rule, does it ever give you negative areas?

If so, can you predict which vector pairs have this effect?

Getting Started

Try drawing a rectangle around the parallelogram. If you can work out the area of the rectangle and the areas of the parts of the rectangle outside the parallelogram, then you should be able to find the area of the parallelogram.

Don't forget that you can break up complicated shapes into simpler small shapes (such as triangles and rectangles) whose areas are easier to find.

Student Solutions

Tony sent us his answers to the first parts.

(a) $6$ units squared ($=3\times 2-0\times 5$)

$$a d-b c\ \text{ (or } bc-ad\text{ if } bc>ad)$$

Here's one way to work that out.

$$a b+b c+a d+c d-a b-b c-b c-c d=a d-b c$$

Teachers' Resources

Why do this problem?

The problem looks as though it is about vectors and area formulae. It diverts via alternative methods for finding area, into observing, then systematically hunting down a numerical relationship, proving this algebraically and geometrically, and testing where the proofs are valid. It also relates to determinants of matrices which students may encounter in later years.

Possible approach

You may be interested in our collection Dotty Grids - an Opportunity for Exploration, which offers a variety of starting points that can lead to geometric insights.

As students enter, they can work on the two introductory parallelograms, and any other examples with one vector along an axis. You could have a permanent prompt written in the corner of the board "do you know what the next question ought to be?"

Stop the group after most students begin to realise how the numbers in the vectors are linked to the areas. Ask for clear statements of observations/conjectures or, if appropriate, theorems+proofs.

Probably someone in the class will establish the next thing to do - but if not: "it seems that the numbers in the vectors are linked to the area of the parallelograms, is it true for all vectors? If so what is the link? Can we prove it?

What do you think we need to do next? Does anyone have any questions?"

"Try these two examples and see what happens." Expect that some students will realise that they do have questions - how to find the height and base (or the area) in this tilted context. If this is a general concern, make the question public, and ask the group to divert and work on finding a good technique.

Allow time for pairs to generate plenty of examples, searching for the rule. Ecourage them to collaborate by telling their partner what they think each area will be, before they work it out. Both partners should be convinced by the rule.

As individual pairs become convinced, ask what the next question should be. It's hard to control 4 variables, can they fix three and let one vary? Can they go straight to analysing the general situation?

As a teacher, when you overhear good questions between students, write these on the board, as prompts/ models of good practice for the others.

Bring the group together with sufficient time to work together understanding the diagram in the solution, generating the algebra, and manipulating the terms. Ideally, the teacher need only show the diagram, and then let students suggest the next question, and the next question as the group find answers. The teacher's role here is to keep everyone together, make helpful suggestions where necessary and make sure the group doesn't go off track.

Key questions

How did you get that area?

What should the next question be?

Possible support

Alternative problems with areas on an integer grid, are isosceles triangles, and tilted squares. Both of these require investigative, systematic, shape work, and relate directly into familiar mathematics.

Possible extension

The diagram used above doesn't seem to apply to a situation with a, b, c, or d negative. Take a numerical example with at least one negative, adapt the area diagram to summarise a general case. Will the algebra still work out? How many cases would you need to prove it geometrically? How many cases would you need to solve it algebraically?