Introduction

If you want a very simple introduction to truth tables you

might like to start with

Truth Tables and Electronic Circuits but this article also

provides an introduction to the subject and does not assume any

prior knowledge of truth tables or circuits.

In this article you will find explanations of circuits

and how they correspond to the logical language we use

to discuss mathematics. You will be challenged to

summarise the workings of the circuits by filling in

blanks in the corresponding truth tables. To check your

answers you can then switch to

another version of this article which has all the

truth tables complete.

This diagram gives a summary of the information you

will need to build your own circuits.

|

|

This is the first of a series of articles on mathematical logic which

will show that truth tables, set theory, Boolean algebra and electronic

circuits are essentially equivalent; that is, theorems that can be

proved in one system have their counterparts in the other systems.

In subsequent articles we shall see how Boolean algebra is used in

designing electronic circuits. In this article we begin to explore

the links between electronic circuits and mathematical logic.

Although logic does not model language perfectly it does form a

useful system that, in practice, is the basis of most of the

communication of mathematical ideas between working mathematicians.

Logical conventions are used to overcome the ambiguities and

inadequacies of language. The philosophical aspects of the subject

are rather more subtle and complicated and we shall not dwell on

them.

A proposition is a statement that has exactly one of the

truth values 'true' or 'false'. A propositional function is

a sentence involving variables, for example "She is the Queen of

England" and "x is greater than 7". These functions become

propositions when meanings are substituted for the variables

('she' and 'x' in the above examples).

Before we go on to experiment with circuits we need a notation

to record and summarize the combinations of propositions used in

logical arguments and also the combinations of switches used in

circuits.

We use small letters

to represent propositions. If

the proposition

is true it is said to have the truth value 1

(or sometimes T) and if false the truth value 0 (or F). Propositional

logic is concerned with compound propositions formed from given

propositions by means of the connectives 'not', 'and', 'or',

'if ... then' and combinations of these connectives, for example

'if and only if'.

In circuit diagrams each switch is either 'on' (representing the

number 1) or 'off' (representing the number 0). Combinations of

switches called logical gates represent the logical

connectives.

Logical arguments are a combination of propositions, and circuits

are a combination of switches that control the flow of current.

Modern computers not only store data in the form of '0's and '1's,

on which they perform arithmetic, but perform many highly

complex tasks that we have come to take for granted. Studying the

relation between truth tables and circuits will help us to

understand a little of the underlying principles behind the design

and programming of computers.

Negation

Now it is time to use

Circuit Maker

to make some of your own

circuits and find out how the logic gates work.

|

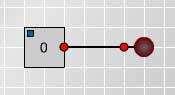

First, connect a switch to a lamp

as in Fig. 1 and click on the

switch several

times to change it from 1 to 0 and

back to 1. Observe that the light

goes on when the switch registers

1 and the light goes off when the

switch registers 0.

|

Fig. 1

|

|

Fig. 2

|

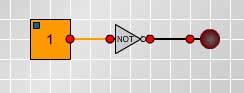

Now put a NOT gate into the

circuit between the switch and

the lamp, as shown in Fig. 2, and

observe what happens when you

change the switch from 1 to 0.

|

Given a proposition

, the negation not-

, written

,

is the proposition demonstrated by this circuit and defined by the

following truth table.

Conjunction

The logical connective 'and' is used to make a compound proposition

from two component propositions. For example if we speak the truth

when we say "Today is Friday and it is raining" then both of the

component propositions are true. If either or both are false

then the compound proposition is false.

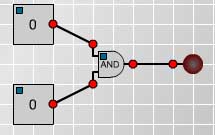

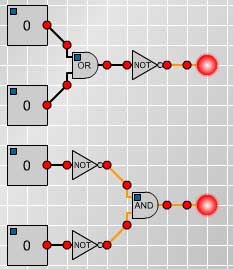

|

Make and test the circuit

shown in Fig 3. and fill in

the truth table replacing

the question marks with

1's to record when the lamp

lights up and 0's to record

when the lamp goes off.

|

Fig. 3

|

|

If you want to check your work then you can click

here to get the article with all the blanks filled in.

Disjunction

In everyday language we often use 'or' inclusively as in Ïf you want to buy

cereals or soft drinks go to aisle 7 in the supermarket" when we expect people

who want to buy both cereals and soft drinks to go to that aisle as well as

people wanting to buy just one of them. On other occasions we use 'or'

exclusively to offer two alternatives expecting the listener to choose

just one of them as in "Do you want steak for dinner or chicken?". The meaning

is usually clear from the context but to avoid any ambiguity in mathematics

the logical connective 'or' is always used inclusively and never exclusively.

Given any two propositions

and

the disjunction

or

,

(written

)is given in the following truth table.

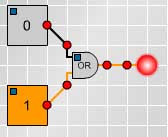

|

Fig.4

|

Make the circuit shown

in Fig 4. and fill in

the blanks in the truth

table replacing the

question marks with 1's

and 0's..

|

|

Again you can check your work by clicking

here.

|

Fig. 5

|

|

|

|

Again you can check your work by clicking

here.

|

|

XOR, NAND, NOR and XNOR Next we investigate some of the other logical gates used

in circuitry. Then we shall discuss other important logical connectives

such as 'implies', often expressed as 'if... then' as in

" if I go to the shops then I'll buy you some ice-cream".

After that we shall be able to relate the circuits to the

language of logical arguments and also see how circuits can be built to

perform simple operations such as addition.

Now experiment with the circuits for XOR, NAND, NOR and XNOR and complete

the following truth table replacing the question marks with 1's and 0's.

|

|

Comparing these tables to what we have already discovered we see that p NOR q

means 'not(p or q)', that is

, and it is also equivalent to

.

Also p NAND q means 'not(p and q)', that is

,

and it is also equivalent to

.

You can check the truth tables for XOR, NAND, NOR and XNOR by

clicking

here.

Implication Thinking about what we mean by 'if p then q' we see that this rules out the

possibility that p is true and q is false. If I make the promise " if I go to

the shops then I'll buy you some ice-cream" but I go to the shop and do not

buy the ice-cream then I have broken my promise. So, denoting 'if p then q'

by

, the truth table for 'if p then q' must include the line:

As the following example shows true conclusions can be proved by valid

arguments from false premises and so we should expect 'false

true'

to be true.

We shall prove the proposition '2=1

2=2'. Of course 2=2 is true

(by definition) but the following argument proves this as a consequence of a

false hypothesis.

By the symmetry of equality if 2=1 then 1=2. By the transitivity of equality

it follows that, having shown 2=1 and 1 = 2, then 2 = 2.

This establishes a second line in the truth table for implication.

There might still be some doubt in the reader's mind about why the definition

of 'false' implies 'true' is 'true'. It could not be false because then we

would have

logically the same as

which is

not the case. Consider for example

which is true whereas

is false, so we have no choice but to make this

definition for

. Also 'if x then x' is true whether x is true or false so we must have the

complete truth table as follows.

It is convenient to have a single connective which combines

and

. This connective is the bi-conditional

'p if and only if q' (written

)and defined by

the truth table:

We observe that in the truth table for

this compound

proposition is true precisely in those circumstances in which p and q have

the same truth values and this is given by the logic gate p XNOR q. Also

observe that the logic gate p XOR q is equivalent to

.

Note that p XOR q is 'the exclusive or', true when

either p is true or when q is true but not when they are both true. In

everyday language we often use the exclusive or, as in "do you want steak or

chicken for dinner?", but to the mathematician who, by convention, uses only

the inclusive or, the logical answer is " yes" if he wants meat for dinner

and "no" if he does not want meat.

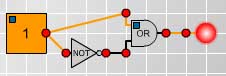

Tautologies If the truth value of a compound proposition is always true for all possible

combinations of truth values of the given propositions, then the compound

proposition is called a tautology. The following truth table and circuit show

that

is a tautology. This is called the Law of the

Excluded Middle because either

is true or

is true and there is

no third alternative.

The Sheffer stroke

The five connectives

can be

defined by one symbol called the Sheffer stroke which was devised by

H.M.Sheffer in 1913. At the time it was simply a piece of pure mathematics,

but later it has had applications in designing electronic circuits from

assemblies of a single component, the NAND gate. We have already seen that

p NAND q is equivalent to 'not p or not q' or, equivalently, 'not (p and q)'

and that it has the following truth table.

|

|

The negation

is equivalent to p NAND p.

The disjunction

is equivalent to

.

Can you make up three circuits, using only the NAND gate, that are equivalent

to the conjunction

, to the conditional

and to the

bi-conditional

?

If you have worked through this article you should now be able to

solve the problems

Simple Counting Machine,

Adding Machine and

Circular Circuitry and not just by trial and error, and you

should be able to explain the circuits.