A proof of a mathematical statement is a logical argument that

shows the statement is true according to certain accepted

standards.

The idea of proving a statement is true is said to have begun in

about the 5th century BCE in Greece where philosophers developed

a way of convincing each other of the truth of particular

mathematical statements. They had to agree definitions of certain

basic ideas (e.g. point, line, surface), and axioms [see note 1 below ] which were

statements about the starting points (e.g. that it is possible to

draw a circle of any radius). Over time these ideas and many

others were developed in geometrical form, and finally collected

and organised in thirteen Books by Euclid (325-263 BCE) in what

was called his "Elements of Mathematics".

Ideally, the proof of a statement in any particular branch of

mathematics uses the rules, definitions, axioms and theorems of

that branch of mathematics, together with the rules of logic.

Even though arithmetic, algebra and geometry each have different

rules and procedures, we use the same kind of logic for each of

them.

Direct and Indirect Proof.

Direct Proof

Direct Proof is possible if we have agreed axioms and

definitions to start from and an agreed method (a logical

argument) that enables us to proceed logically step by step

from what we know to what we do not know, but think is true.For

example, propositions 5 and 6 in Euclid Book I are about the

equality of the base angles of an isosceles triangle

[see note 2 below ].

This is "obviously" true, but still has to be proved from first

principles.

For some more difficult problems mathematicians developed a

method of "working backwards". This works by assuming that the

desired result is true, and showing that the consequences of

that assumption are consistent with known facts and the basic

principles. The final proof still had to be written out in the

correct order.

Constructive proof is another form of direct proof. This is

where an object has to be directly constructed from the basic

elements of the system. There are many constructive proofs in

Euclid Book I. Proposition 1 for example, shows how to

construct an equilateral triangle [see note 3 below ].

However, it is not always possible to prove something by

keeping to the strict rules of direct proof, and so

mathematicians devised forms of indirect proof to achieve

results.

Indirect Proof

Indirect proof means that we try to find a way of obtaining a

result in some "round about" way. One way is by supposing that

if the result we are looking for is not true, then the starting

point cannot be true. [see

note 4 below ]

Reductio ad Absurdum or Reduction to the Absurd

[

see note 5 below ] is

another method of indirect proof where we try to show the

opposite of the proposition to be true, but as soon as we come

to a situation in the argument that we know is impossible, then

we can say that the original proposition was true.

The proof that the square root of two is not rational

[s

ee note 6 below ] is

a classic problem where an Indirect Proof is used. A proof

originally attributed to Aristotle (384-322 BCE), uses basic

ideas of arithmetic. This proposes that the diagonal of a

square can be represented by a rational fraction, and produces

an argument that constructs a number that is both even and odd

(which is not possible of course).

In the 5th and 6th centuries BCE, the Pythagoreans [see note 7 below ] were interested

in finding a common measure for the side of a square and its

diagonal and discovered that these two lengths were

incommensurable [see note 8

below ] by using a geometrical construction. In

geometrical terms, this can be demonstrated by the successive

subtraction of the smaller length from the larger:

In the red square in Figure I, BD = AB (=AC) and if BC (the

diagonal) and AC (the side) have a common measure it must also

be a common measure for CD = BC-BD.

Now AB' = B'D = DC

And B'C = AC - AB'. So B'C must also have the same common

measure.

So, in the green square, the diagonal B'C and the side DC have

the same common measure. By the same argument as for the red

square, DC' minus DD' leaves D'C' (which again has the same

common measure). This means that no matter what the size of the

square, the common measure will always be the same.

[See note 9 below ]

This is an indirect proof, because it shows that the process

goes on forever producing a lower limit which is zero -

contradicting the idea that a common measure can be found.

|

|

Diagram I

|

In order to overcome some of the difficulties experienced by the Pythagoreans,

Euclid ( in Book X of his Elements) showed how to manage the mathematics of

incommensurables like

, etc, [See note 10

below ] purely by geometrical constructions.

Keeping to the rules?

However, even in Euclid's Book I, the first proposition about

congruent triangles [See note

11 below ], there were unsubstantiated assumptions.

Euclid used the idea of "superposing" one triangle on another

by a kind of transformation, but there are no postulates or

definitions about what is meant by this action. In other words,

even Euclid used an idea that was not fully justified.

It is now recognised that Archimedes (287-212 BCE) developed

his own methods for calculating difficult results about areas

and volumes enclosed by curves and surfaces, and then rewrote

them in terms of the standard geometrical procedures of the

time [See note 12

below ]. In a letter to a friend he said,

"I set myself the task of communicating to you a certain

geometrical theorem which had not been investigated before but

has now been investigated by me, and which I first discovered

by means of mechanics and then exhibited by means of geometry."

In his first proof of the area of a parabolic segment,

Archimedes used his discovery of the properties of the lever to

balance the weight of a segment of a parabola against the weight of

a triangle. In his second proof he used the method of exhaustion to

show that the area of the segment was

that of the triangle.

So, the ideal proof methods set up by the earliest European

mathematicians were not always adhered to, and later we will see

that other mathematicians were still breaking the rules in order

to achieve new results.

In the early ideas of the calculus, Cavalieri (1598-1647) and

others adapted Archimedes' method of exhaustion to develop the

method of "indivisibles". These were conceived of as infinitely

small elements of lines, surfaces or volumes. Arguing by

analogy, a line was made up of points, a surface was made from

lines, as in the weave of cloth, and a volume thought of as a

pile of very thin sheets of paper. In this way, areas and

volumes of new objects could be compared with areas and volumes

of known objects by a process of transformation.

For example, the area of a

triangle was thought of as a very large number of very thin

parallel lines. These were called 'Line Infinitesimals'. Areas

of triangles on the same base and between the same parallels

are equal. If each line remains the same total length, then the

areas of the irregular shapes are the same as the area of the

triangle s.

Throughout the 17th century, "proof by

demonstration" was common.

The general idea was, "If

I show you enough examples of how the algorithm works, then you

will be convinced'.

Mathematicians demonstrated how they achieved their results in

the early calculus by showing diagrams of curves, and

sufficient examples of the procedures to convince their

audience. In most cases the truth of the result was established

by it's practical application, or that it achieved the same

results as already known by a geometrical method. These

experiments and demonstrations aided the discovery of

interesting and important results, but did not conform to the

strict standards of proof because they were based on

unjustified assumptions about the very small quantities

eventually "disappearing".

Many mathematicians were uncomfortable with this situation, but

a logical basis for the calculus methods did not appear until

the middle of the 19th century.

|

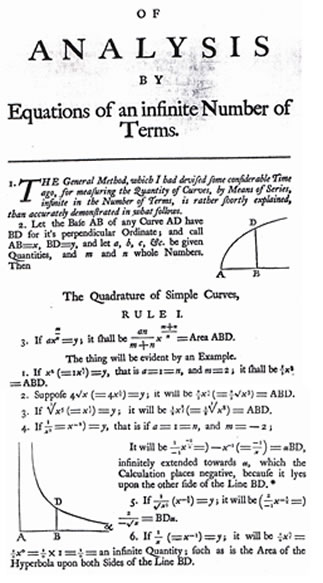

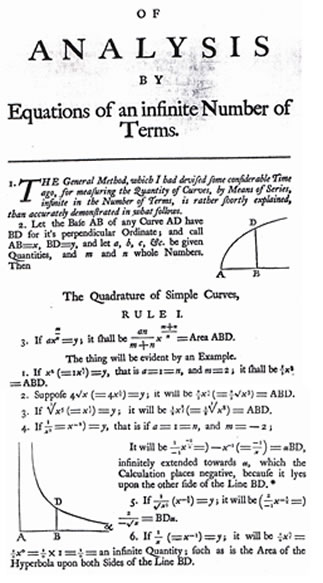

This is part of the first English Edition of Newton's

method for discovering the areas under curves using his

method of infinite series published in 1745.

This is the general rule for what we now call

'integration' in the calculus.

Newton gives

examples to demonstrate how it works with different

algebraic expressions. .

|

When mathematicians like La Hire (1640-1718) and Chasles

(1793-1880) began to develop projective geometry, they used a

method called "projection and section" to show that many

Euclidean proofs were also valid in the new geometry. For

example, it was well known that the ellipse could be obtained

by taking a section through a cone, so why not think of the

ellipse as a transformation of a circle and look for the

properties which remain the same? [See note 13 below ]

|

|

For example, making an oblique cut on a circular cone produces

an ellipse. By the method of 'Projection and Section' we can

imagine the ellipse as the 'shadow' of the circle on a plane.

Brianchon's (1783-1864) theorem states that if six vertices of

a hexagon on a circle are joined as in the diagram, the

intersections of the chords joining the points as shown lie in

a straight line. The same result is also true for the ellipse

or any other conic section. This is related to Pascal's theorem

where the three points of intersection of the opposite sides of

a hexagon lie in a straight line.

Imre Lakatos, in his Proofs

and Refutations tells the story of the way the proof of

the Descartes-Euler conjecture (F + V = E + 2) about counting

the Faces, Vertices and Edges of polyhedra [see note 14 below ] was challenged

by scientists working in the new field of crystallography, and

how the original definition of a polyhedron had to be changed

[see note 15 below ].

For example, it is possible to grow isomorphic [see note 16

below] crystals, one 'inside' another and there is a good

argument to suggest that the conjecture might not be valid in

this case. There are many examples where counterexamples of

mathematical propositions have come from the physical world and

mathematicians have had to re-think their theories.

|

The blue cube and the yellow cube are isomorphic.

Can this be one polyhedron or two?

So F + V = E + 4?

What about a tetrahedron inside another tetrahedron?

|

In recent times, computers have been used to investigate

solutions of difficult mathematical problems and one was used

to tackle the proof of the famous Four Colour Theorem using a

program to enumerate all possible maps [see note 17 below ]. The big

question was since all proofs up to this time had been proved

by people, was the fact that it had been completed by a

computer a valid proof or not, and how could anyone be sure the

computer had covered all the possible cases? This kind of

counting procedure is called proof by

enumeration or proof by

exhaustion .

Proof by experiment or

showing examples has always been a problem, as we have seen

with the polyhedra and the maps, since we never know whether we

have all the possibilities or when somebody will discover a

counterexample. We need clear definitions and logical argument

based on agreed facts to provide a sound proof.

Today, mathematicians have many ways of tackling proofs by

using one system to help them find results in another. For

example, Pythagoras' Theorem can be regarded as an arithmetic

relation, an algebraic generalisation, a formula in

trigonometry, or as geometric property. Each of these

approaches gives different insights into the wide range and

application of the general idea.

For this to work, it is

important to be sure that the fundamental properties remain

invariant as we transform the problem from one system to

another.

Wise Men from the East

Recently, important research in ancient Hindu and Chinese

mathematics has uncovered some very different attitudes to

"proving" results. Besides making their own original

contributions, mathematicians wrote Commentaries on the works

of earlier writers to elaborate ideas, to find other ways of

achieving results, and of making new and useful applications.

It is now clear that other cultures have produced ways of

finding "truths" and generalisations quite different from

Aristotle's logic.

Indian Mathematics

Many Indian writers who produced original mathematics, also

took great pains to write commentaries on their own works and

on works of earlier scholars. By the time of Bhaskaracharya

(1114-1185) [see note 18

below ], Indian mathematicians had achieved an

understanding of number systems and solution of equations which

was well ahead of the Europeans. It is in their commentaries

that we find detailed proofs and demonstrations of their

results and discussion of appropriate methods. Until recently,

much of this was obscured by superficial interpretation and

misunderstandings of the cultural context [see note 19 below ].

|

An ancient Indian text, the 'Sulbasutra' (meaning

'Rope-Measuring') shows how to use two different size

squares to find the area of a square which is the sum

of the two areas.

By discussing

this diagram, students were able to justify and extend

this method, thus discovering many geometrical

properties much earlier than the Greek

mathematicians .

|

Chinese Mathematics

The most important classic of Chinese mathematics is

The Nine Chapters on the

Mathematical Art which was written some time in the 1st

century CE. Liu Hui (265-316 CE) wrote an important commentary

on this work, and recent research shows us that there are other

methods of investigating mathematical ideas other than the

commonly accepted proof methods of Euclid. During this period

in China, mathematics proceeded as a discussion between master

and student who together focussed on the diagram; its

appearances and possibilities. This shows that deduction from

first principles is not the only model for the discovery and

checking of mathematical results. This is a model of

mathematical reasoning quite different from that of Euclid, but

just as important and fundamental with the aim of

generalisation rather than abstraction, and of deeper

understanding rather than logical proof.

|

This right-angled triangle comes from Lui Hui's

commentary on the 'Nine Chapters'.

By using some simple geometry students were able to

find the area of the triangle and a number of other

relations between the lines and the other areas in the

diagram. This was done quite independently from the

Greek geometers.

|

For pedagogical notes

Use the notes tab at the top of this article or

click here .

Notes

- The Greek word 'axiom' means an agreed starting point.

The word 'postulate' is also used to describe 'what is

possible', or what basic ideas can be used.

- Proposition 5 used to be called the 'Pons Asinorum' (the

Bridge of Asses) because it was once regarded as a test of

understanding for the rest of the Elements.

- This proof has been criticised because Euclid has no

axiom which states that there is a point of intersection when

two lines cross.

- This is often called the contrapositive argument. i.e. If

p implies q, then 'not q' implies 'not p'.

- Some mathematicians choose to call 'reductio ad absurdum'

orproof by contradiction, but others have decided it is a

separate case.

-

A rational number is any one that can be represented by a

fraction, like:

- Pythagoras (c.569-475 BCE) founded a society which

continued well into the 5th century.

- In-commensurable means that there is no common measure

between two given lengths.In this case, a side of a square

and its diagonal cannot be measured exactly in the same

units, or fractions of the unit.

- In this case, a side of a square and its diagonal cannot

be measured exactly in the same units, or fractions of the

unit.

See Pedagogical Notes and Questions 1(c) .

- Another name for these numbers is 'surds'.

- For details on Euclid see D.E. Joyce's commentary at

weblink EUC

- See Netz and Noel (2007) for the most startling recent

discoveries about Archimedes.

- In this kind of projection, the lengths of lines and the

shapes of curves change, but the order in which points are

connected, remains the same.The term invariant refers to properties

that remain the same under some kind of transformation.

- The original conjecture by Descartes was investigated by

Euler in 1758 when attempting to classify polyhedra.

- The publication of Lakatos' original thesis in 1961 was a

major factor in the development of Investigations in school

mathematics.

- Iso-morphic means the 'same shape'. Isomorphic crystals

of chemicals with similar composition can grow on each

another, as often seen in the school science laboratory.

- See Robin Wilson's Four

Colours Suffice (2002). This is the history of the map

colouring problem first proposed by a student of Augustus De

Morgan in 1852. The first proof in 1976 counted 1,936

different maps, but after re-testing the program and

discovering mistakes, by 1994 the number had been reduced to

633. There are still some people who doubt the result.

- Known also as Bhaskara II or 'Bhaskhara the

Teacher'.

- In the early 20th century, Hardy, and others at Cambridge

found many of the results of the brilliant Indian

mathematician Ramanujan (1887-1920) difficult to understand

because the proof methods were unlike anything they had seen

before. Even today, mathematicians are still discovering

important new results from the work of Ramanujan.

References

Berggren, J. L. (2003) Episodes in the Mathematics of

Mediaeval Islam New York, Berlin. Springer (original 1986)

D'Amore, B. (2005) Secondary school students' mathematical

argumentation and Indian Logic (Nyaya).For the Learning of

Mathematics 25 (2) July 2005 (26, 32)

Datta, B. ; Singh, A. N.(1935) History of Hindu mathematics,

a source book. Lahore,: Motilal Banarsi Das. (Reprinted by

Bharatiya Kala Prakashan, Delhi)

Dauben, J.W. (2007) Chinese Mathematics in Katz, V. J. (ed.)

Sourcebook (187-384)

Lakatos, I. (1976) (Eds. Worrall, J. and Zahar, E.) Proofs

and Refutations: The Logic of Mathematical Discovery London.

Cambridge University Press

Kanigel, R. The Man Who Knew Infinity: A Life of the Genius

Ramanujan Johns Hopkins Univerity Press

Katz, V. J. (2007) (ed.) The Mathematics of Egypt,

Mesopotamia, China, India and Islam: A Sourcebook. Princeton

and Oxford. Princeton University Press

Keller, Agathe (2005) Making diagrams speak, in Bhskara I 's

commentary of the Aryabhatiya. Historia Mathematica 32:

275-302.

Keller, Olivier. (2006) Une Archeologie de la Geometrie (An

Archeology of Geometry) Paris. Vuibert

Martzoff, J-C. (1987) A History of Chinese Mathematics

Berlin, New York. Springer

Newton, Isaac. (1745) Sir Isaac Newton's Two Treatises on the

Quadrature of Curves, and Analysis by Equations of an

infinite Number of Terms explained: London John Stewart

Netz, R. and Noel, W (2007) The Archimedes Codex. London.

Weidenfeld & Nicolson

Plofker, K. (2007) Mathematics in India in Katz, V. J.,

Sourcebook (385-514)

Li Yan and Du Shiran (1987) Chinese Mathematics : A Concise

History. John N. Crossley, J.N. and Lun, A.W.C. Oxford.

Oxford Science Publications.

Watson, A. and Mason, J. (1998) Questions and Prompts for

Mathematical Thinking Derby. Association of Teachers of

Mathematics

Wilson, R. (2002) Four Colours Suffice: How the Map Problem

was Solved London. Penguin Books

Web Links

For India and China, there are resources on the French

website:

http://www.dma.ens.fr/culturemath/index.html

. The outstanding scholars here are Agathe Keller for India

and Karine Chemla for China. There is very little from these

two researchers available in English at the moment.

She has also set up a History section on the NCETM website

at:

http://www.ncetm.org.uk/ and

then search for the History of Mathematics Community