The Question

|

What are numbers? Most people, even five year olds,

can answer that question to their own satisfaction. Many

different answers are given to this question, all more or

less acceptable within the discourse taking place.

Although negative, fractional and irrational numbers were

accepted by scholars in Europe in the sixteenth century,

and earlier in ancient civilisations in other parts of

the world, until the nineteenth century negative numbers

and complex numbers were often disparagingly referred to

as absurd numbers and imaginary numbers. These numbers

now play an essential part in mathematics, even school

mathematics, and schoolchildren learn about them.

|

This brief descriptive article is intended as light reading for

the general reader. Here we shall explore the question in a

very informal way. We shall discuss different sets of numbers,

including quaternions and a brief mention of Clifford Algebras,

starting with counting numbers and meeting new sets of numbers,

each set containing within it the set of numbers discussed so

far. Quaternions are explored in more detail in the NRICH

problem

Two and Four Dimensional Numbers

In order to understand why there are different sorts of

numbers, and what they are, we need to consider how young

people meet the familiar number systems and how we broaden our

ideas of number as we learn more arithmetic. Many small

children are proud of themselves when they can count to one

hundred and a little later they have an experience of awe and

wonder when then first appreciate that counting goes on for

ever with no end. These children have a familiarity with

counting and the natural numbers, even with the concept of

infinity, before they meet a number system. Roughly speaking a

number system is a set of entities that can be combined,

according to agreed rules, by the operations of addition,

subtraction, multiplication and division, always producing

answers that are in the set.

Rules of Arithmetic

|

Adding and sharing are transactions that we engage in

early in our lives and they take us beyond simple

counting into the realm of arithmetic. So we should

define numbers to be more than labels for naming and

recording the size of collections of objects that we have

counted. We need to think of numbers as entities that can

be combined according to an agreed set of rules which we

call arithmetic. The more we know about and use this

arithmetic, the more we appreciate that it can be

generalised and refined into more and more useful

mathematical tools for solving human problems of all

sorts.

|

|

If we use numbers to describe the size of a collection

of objects we need a number for a set that has nothing in

it. So we need to expand our concept of number to include

zero. While the use of numbers, including place value,

dates back at least five thousand years, scholars in

Europe were still debating whether zero could be a number

as recently as five hundred years ago.

|

Inverses

Once we have an operation which combines two numbers to give another number,

can we undo that process? If we can add 7 what is the operation on the answer

which restores it to the original number?

|

Subtraction is another natural idea based on concrete

experience, not of increasing the size of a collection of

objects by combining two collections, but of reducing the

size of a collection by removing some of the objects. If

we have 5 coins and we need 12 to buy something we can

ask how many more coins do we need, which number do we

add to five to make 12; this is equivalent to finding the

answer to 12 - 5, but what number do we add to 13 to make

9 or what is the answer to 9 - 13? If we say that there

is no answer to such subtractions then it is only because

we do not know about negative numbers. Once negative

numbers come onto the scene we have many uses for

them.

|

We can do arithmetic without knowing the mathematical language and nothing

so far is beyond the experience of a small child learning to read a

thermometer on a wintry day.

We can think of any subtraction as simply the addition of two integers so

subtraction is not essential to recording arithmetic operations. For example

9 - 13 = 9 + (-13) = -4. The integer -13 is called the inverse of the +13

because (+13) + (-13) = 0. Every integer has an inverse such that the number

added to its inverse gives zero. We are already working with the structure

and using the rules which define the arithmetic involved in adding integers.

This is an example of a mathematical structure called a group.

From the Natural Numbers to the Integers

Another way to explain the evolution of thinking that extends ideas of

counting and addition is to say that if we want to be able to solve all

equations of the form a + x = b, where a and b are given and we have to find x,

then for all such equations to have solutions we need to work in the set of

integers. For example 9 + x = 5 had no solution within the set of counting

numbers.

Rational Numbers

|

In the same way as horizons are extended to include

negative numbers it is also everyone's experience to

learn that fractions are also numbers. Mathematicians

call these numbers rational numbers . Children are

interested in 'fair shares' even before they start school

so division is also based on concrete experience.

|

Addition and subtraction are inverse operations inextricably connected.

Similarly multiplication and division are inverse operations in the sense

that 5 ×4 = 20 and 20 ¸4 = 5.

It is not until we can work with the set of rational numbers that every

addition, subtraction, multiplication and division of two numbers in the

set gives an answer that is also a number in the set giving a 'self contained'

number system. The rules for the arithmetic of rational numbers

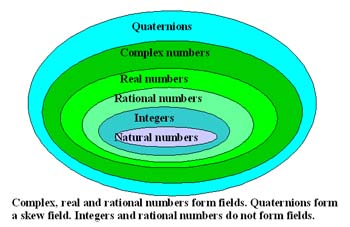

are simple. This set of rules defines what mathematicians call a field.

(1) The set of rational numbers is closed under addition, and associative,

the rational number zero is the additive identity and every rational number

has an additive inverse. We say rational numbers form a commutative group

under addition.

(2) The set of rational numbers, leaving out the number zero, is closed under

multiplication, and associative, the rational number one is the multiplicative

identity and every rational number in this set has a multiplictive inverse.

We say the rational numbers, leaving out the number zero, form a commutative

group under multiplication.

(3) When we add and multiply rational numbers we use the distributive law.

For example

|

3×(4 + 5) = 3 ×4 + 3 ×5 = 27. |

|

We need to extend our ideas of the arithmetic of whole numbers to include

fractions (rational numbers) because we cannot solve all equations of the

form ax = b, where a, b and x are integers, a and b are given and we have

to find x. If a, b and x are rational numbers then all such equations have

solutions.

Irrational Numbers

Many people use only rational numbers because, even though no rational

number will give exact measurements of even simple shapes, exact measurements

can be approximated to a high degree of accuracy by rational numbers. The

length of the diagonal of a unit square is Ö2 and this is an irrational

number, one that cannot be written as the quotient of two integers. It is

approximately 1.414 but it cannot be given exactly however many decimal places

we use. See the interactive proof sorter for the proof that

Real Numbers The rational and irrational numbers together make up the real

numbers. Each real number corresponds to exactly one point on a line and all

the points on that line are represented by real numbers. We call this line

the real line. The real numbers are equivalent to one dimensional vectors

and, together with addition and multiplication, form a field. We have now

discussed two different examples of fields of numbers, the rationals

and the reals.

Complex Numbers

In the field of real numbers we can solve the equation x2 = a only when

a is positive but not when a is negative. Real numbers are good enough for

many mathematical purposes but clearly they have limitations. It is necessary to

recognise the existence of two dimensional numbers, the complex numbers, in order

to solve all quadratic equations. See

Real Numbers The rational and irrational numbers together make up the real

numbers. Each real number corresponds to exactly one point on a line and all

the points on that line are represented by real numbers. We call this line

the real line. The real numbers are equivalent to one dimensional vectors

and, together with addition and multiplication, form a field. We have now

discussed two different examples of fields of numbers, the rationals

and the reals.

Complex Numbers

In the field of real numbers we can solve the equation x2 = a only when

a is positive but not when a is negative. Real numbers are good enough for

many mathematical purposes but clearly they have limitations. It is necessary to

recognise the existence of two dimensional numbers, the complex numbers, in order

to solve all quadratic equations. See

In 1799 Gauss proved the Fundamental Theorem of Algebra: every polynomial

equation over the complex numbers has a full set of complex solutions. Then,

and finally, complex numbers were completely accepted as 'proper' numbers.

This theorem means that every quadratic equation has two solutions, every

cubic has three and so on.

What else can we do with complex numbers? Complex numbers are two dimensional;

whereas real numbers correspond to points on a line, complex numbers correspond

to points in the plane. The complex number written as x+yi corresponds to

the point in the plane with coordinates (x,y). Let us examine the

significance of this mysterious i referred to as an 'imaginary' number.

What role does it play?

Complex Numbers and Rotations

Think about taking a real number and finding its additive inverse, say

5 and -5. To move from any real number to its additive inverse we must multiply

by -1, or to think of it another way, we must move from the positive real axis

to the negative real axis, a half turn about the origin so the point (5, 0)

moves to (-5,0), that is the complex number 5+ [0×i] moves to

-5+[0×i]. No obvious clue there as to the role of i but let's

probe a bit further and think more about rotations. Two quarter turns make

a half turn so what happens when we rotate the plane by a quarter turn

about the origin? The point (5, 0) moves to (0,5), that is the complex

number 5 + [0×i] moves to the complex number 0 + 5 i which appears

to be equivalent to multiplying by i, that is i(5 + [0×i] ) = 0 + 5i.

(It is not necessary to write in [0×i] here but we do so to make

clear how the mappings of the complex numbers correspond to the mappings of

the points in the plane including the points on the real line which correspond

to real numbers.)

We have seen that a real number is mapped to its additive inverse by

multiplying by -1. So if a quarter turn of the complex plane is equivalent

to multiplying by i then a half turn (that is two quarter turns) must be

equivalent to multiplying by i twice which must be the same as

multiplying by -1 and this tells us that i2 = -1. Taking i2 = -1

this fits in with moving (5, 0) to (-5, 0), or correspondingly,

5 + [0×i] to i2(5 + [0×i]) = -5 + [0×i].

A quarter turn moves (0,5) to (-5,0) or equivalently 0 + 5i to

-5+ [0×i] and this time multiplying by i gives

i(0 + 5 i) = 5i2 + [0×i] = -5 + [0×i].

All this works beautifully because i2 = -1. This little complex number,

corresponding to the point (0,1), not only allows all polynomial equations

to have solutions but gives a powerful tool for working with rotations. In the

form x+yi complex numbers can be added, subtracted, multiplied and divided

according the the same rules as elementary arithmetic, that is the complex

numbers form a field. We now have three fields of numbers, the complex

numbers, the reals and the rationals.

Another glimpse of the beauty of complex numbers is seen in the formula

linking geometry, trigonometry

and analysis. This formula involves the important real number e as well

as the complex number i. Students usually meet this formula and use it

in their last year in school if they are preparing to study mathematics,

physics or engineering in higher education. In this formula the angle

q is given in radians and not in degrees but the conversion is a

simple matter because p radians is 180o. If we put q = p

we have the very beautiful result

which connects the important numbers e, i, p and -1 in the simple

little formula

If we put

we have

|

ei[(p)/2] = cos |

p

2

|

+ isin |

p

2

|

= i |

|

which suggests that multiplying by

might be equivalent to rotating the complex plane by an angle q (

as this works for quarter turns and i) and this is indeed the case.

|

If one dimensional real numbers can be generalised to

two dimensional complex numbers and both systems form

fields, the obvious question is "what about higher

dimensional numbers?" |

Three dimensional numbers do not exist

Three dimensional vectors are of fundamental importance in applied mathematics.

They can be added and subtracted but although there are two different types

of vector multiplication, multiplicative inverses do not exist and so the

set of three dimensional vectors do not form a field and cannot be a set of

numbers. To understand the significance of the two alternative definitions of

vector multiplication it is necessary to know about

four dimensional quaternions.

Quaternions

If we think about rotations of the plane, and i as the key to understanding

the essence of complex numbers, what about rotations of 3 dimensional space?

For rotations of the plane that map the plane to itself there is only one

possible axis of rotation which must be perpendicular to the plane. [Without

loss of generality we can take the centre of rotation to be at the origin.]

However in 3 dimensional space there are infinitely many possible axes of

rotation through the origin. If we want to specify an axis of rotation we

need the three coordinates for one other point on the axis. Whereas in the

complex plane we only need one parameter to specify a rotation (the angle

of rotation), in 3 dimensional space we need four parameters (three to specify

the axis of rotation and one to specify the angle of rotation). This takes

us to four dimensions and explains why there are two and four dimensional

numbers, but not three dimensional numbers, and why quaternions provide a

very efficient way to work with rotations of 3 dimensional space.

Quaternions, discovered by the Irish mathematician Sir William Rowan Hamilton

in 1843, have all the properties of a field except that multiplication is not

commutative. Moreover quaternions incorporate three dimensional vectors and

much of vector algebra and provide simple equations for reflections and

rotations in three dimensional space.

As applied mathematics and physics regularly deal with motion in space,

quaternions are very useful. It is a quirk of history that this was not perhaps

fully appreciated at first and vector algebra was invented as a tool to work

with motion in 3 dimensional space and concentrate attention on only 3 dimensions.

However a lot of the simplicity of the equations involving quaternions was

lost as well as sight of the underlying reasons for defining scalar and vector

multiplication in the way they are defined. Nowadays quaternions have come into

their own again as an important tool frequently used in applied mathematics

and theoretical physics. Quaternions are also now widely

used in programming computer graphics because the quaternion algebra

involved in transformations in 3 dimensions is so simple.

Higher Dimensional Numbers

What about higher dimensional numbers? Number theorists work with Clifford

Algebras, named after William Clifford (1845-1879), which generalise complex

numbers and quaternions to dimensions 2, 4, 8, 16... and higher dimensions

(all powers of 2). Some of the properties of a field are lost, for example

quaternions are not commutative under multiplication, but Clifford algebras

are associative. Clifford algebras have important applications in

a variety of areas including geometry and theoretical physics. Other

generalisations are studied for which multiplication is not associative.

This 'big picture' discourse has ranged, without getting too technical, from

kindergarten mathematics to the fringe of research into analysis and

applications of number. There is a wealth of literature to take the reader

further at every level and the links below may provide a useful start on

such a journey of discovery.

Higher Dimensional Numbers

What about higher dimensional numbers? Number theorists work with Clifford

Algebras, named after William Clifford (1845-1879), which generalise complex

numbers and quaternions to dimensions 2, 4, 8, 16... and higher dimensions

(all powers of 2). Some of the properties of a field are lost, for example

quaternions are not commutative under multiplication, but Clifford algebras

are associative. Clifford algebras have important applications in

a variety of areas including geometry and theoretical physics. Other

generalisations are studied for which multiplication is not associative.

This 'big picture' discourse has ranged, without getting too technical, from

kindergarten mathematics to the fringe of research into analysis and

applications of number. There is a wealth of literature to take the reader

further at every level and the links below may provide a useful start on

such a journey of discovery.

Some Further Reading

NRICH Articles:

Plus Articles:

Other websites:

Real Numbers The rational and irrational numbers together make up the real

numbers. Each real number corresponds to exactly one point on a line and all

the points on that line are represented by real numbers. We call this line

the real line. The real numbers are equivalent to one dimensional vectors

and, together with addition and multiplication, form a field. We have now

discussed two different examples of fields of numbers, the rationals

and the reals.

Complex Numbers

In the field of real numbers we can solve the equation x2 = a only when

a is positive but not when a is negative. Real numbers are good enough for

many mathematical purposes but clearly they have limitations. It is necessary to

recognise the existence of two dimensional numbers, the complex numbers, in order

to solve all quadratic equations. See

Real Numbers The rational and irrational numbers together make up the real

numbers. Each real number corresponds to exactly one point on a line and all

the points on that line are represented by real numbers. We call this line

the real line. The real numbers are equivalent to one dimensional vectors

and, together with addition and multiplication, form a field. We have now

discussed two different examples of fields of numbers, the rationals

and the reals.

Complex Numbers

In the field of real numbers we can solve the equation x2 = a only when

a is positive but not when a is negative. Real numbers are good enough for

many mathematical purposes but clearly they have limitations. It is necessary to

recognise the existence of two dimensional numbers, the complex numbers, in order

to solve all quadratic equations. See

Higher Dimensional Numbers

What about higher dimensional numbers? Number theorists work with Clifford

Algebras, named after William Clifford (1845-1879), which generalise complex

numbers and quaternions to dimensions 2, 4, 8, 16... and higher dimensions

(all powers of 2). Some of the properties of a field are lost, for example

quaternions are not commutative under multiplication, but Clifford algebras

are associative. Clifford algebras have important applications in

a variety of areas including geometry and theoretical physics. Other

generalisations are studied for which multiplication is not associative.

This 'big picture' discourse has ranged, without getting too technical, from

kindergarten mathematics to the fringe of research into analysis and

applications of number. There is a wealth of literature to take the reader

further at every level and the links below may provide a useful start on

such a journey of discovery.

Higher Dimensional Numbers

What about higher dimensional numbers? Number theorists work with Clifford

Algebras, named after William Clifford (1845-1879), which generalise complex

numbers and quaternions to dimensions 2, 4, 8, 16... and higher dimensions

(all powers of 2). Some of the properties of a field are lost, for example

quaternions are not commutative under multiplication, but Clifford algebras

are associative. Clifford algebras have important applications in

a variety of areas including geometry and theoretical physics. Other

generalisations are studied for which multiplication is not associative.

This 'big picture' discourse has ranged, without getting too technical, from

kindergarten mathematics to the fringe of research into analysis and

applications of number. There is a wealth of literature to take the reader

further at every level and the links below may provide a useful start on

such a journey of discovery.