Complex numbers can be a difficult topic to break into.

Understanding them often involves accepting what may seem to be

arbitrary rules about a meaningless idea. Only later do the rules

make sense and the meaning, applications and connections to other

areas of Maths and Physics become obvious.

The aim of the "Arrow Arithmetic" and "Twizzles" exercises is to

introduce complex numbers in a new way - as an extension of real

numbers, following on from them more naturally than in the

conventional approach.

Exploring the Number Line

Instead of plunging straight into complex numbers, the problems

begin by taking a fresh look at real numbers - numbers on the

number line - and their arithmetic. Numbers are represented by

a pair of arrows - one wider and one narrower - described as

twizzles. The wider arrow is the unit arrow which defines the

scale. The value of the twizzle is given by the length of the

narrower number arrow and its direction - in the same direction

as the unit arrow for positive numbers and in the opposite

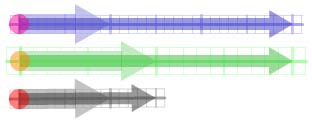

direction for negative numbers. For example, the twizzle below

represents the number two because its number arrow is twice as

long as its unit arrow and points in the same direction.

Figure 1

The interactive animations allow you to manipulate the arrows

by changing their values, moving them around the screen,

stretching them and separating the unit from the number arrows.

To get a handle on their behaviour you could also make

real-life twizzles to manipulate, using strips of elastic band.

Each strip needs three marks on it: one for the origin (the

pink spot in the diagram above), one for the head of the unit

arrow and the third for the head of the number arrow. You can

try the Arrow Arithmethic exercises using elastic twizzles as

well as the virtual ones in the animations.

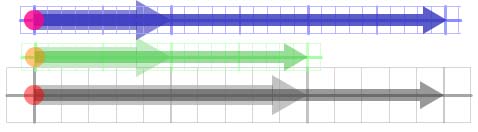

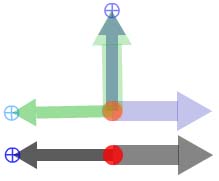

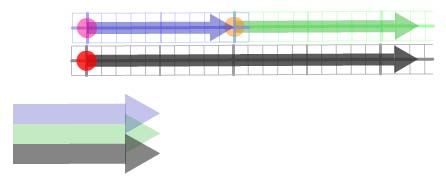

Twizzles can be used to do arithmetic geometrically, with

arrows representing steps along the number line. The simplest

example is addition. To add twizzles, they are first scaled so

that their unit arrows all have the same length and direction.

The number arrows are then arranged nose-to-tail. The twizzle

representing the sum has a unit arrow of the same size and

direction as the original unit arrows and and a number arrow

streching from the tail of the first number arrow to the head

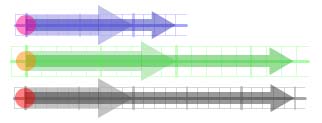

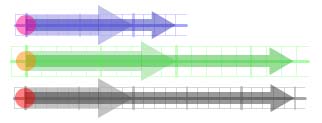

of the last. In Figure 2, the blue and green number arrows have

been added together to give the grey. Below the number arrows

are the unit arrows, lined up to show their matching size and

direction.

Figure 2

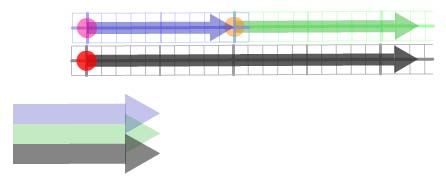

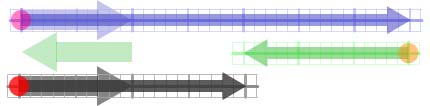

In Figure 3, the green twizzle has been subtracted

from the blue one to give the grey. Because subtraction is just

addition of a negative number, the rule for twizzle subtraction is

similar to addition, except that we must start by rotating the

green twizzle through

to make it negative relative to the blue

unit arrow. The twizzles are then added nose-to-tail as before.

Figure 3

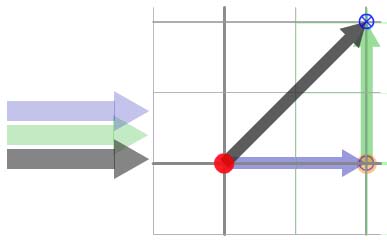

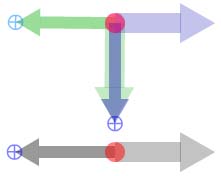

Multiplication is a little different. Figure 4 shows an

example, where the blue and green twizzles are multiplied to

give the grey twizzle. First we adjust the length and direction

of the green unit arrow until they are the same as those of the

blue number arrow. The other two arrows (the unit arrow from

the blue twizzle and the number arrow from the green) make up

the grey twizzle representing the product. We could have got

the same answer by matching the lengths of the blue unit arrow

and the green number arrow, in which case the product would

have been represented by the remaining two arrows.

Figure 4

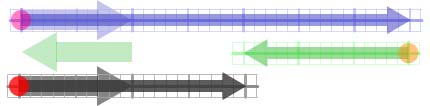

Dividing by a number means multiplying by its reciprocal (one

divided by the number), and to find the reciprocal of a twizzle

you swap the lengths of its arrows. So Figure 5a shows how the

blue twizzle is divided by the green: the roles of the arrows

in the green twizzle have been exchanged so this time we match

the sizes of the number arrows and the two unit arrows make up

the twizzle for the answer. Because we matched the number

arrows, the unit arrow of the blue twizzle becomes the unit

arrow in the result and the unit arrow of the green twizzle

becomes the number arrow in the result. We could also have got

the answer by matching the unit arrows (Figure 5b), but we

would have had to take the green number arrow for the grey unit

arrow and the blue number arrow for the grey number arrow.

Figure 5a

Figure 5b

New Directions

The twizzles we have looked at so far have arrows pointing in

the same or in opposite directions and can represent any number

on the number line. What about twizzles whose arrows point in

completely different directions? These represent numbers not on

the number line - complex numbers. Twizzles can be used to

think about what complex numbers are and how they behave.

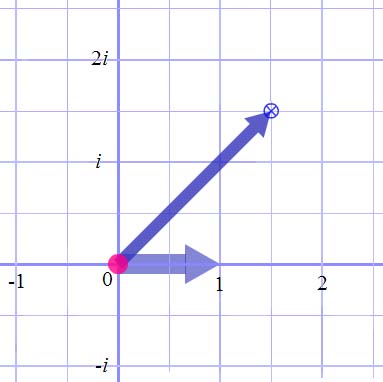

Let's add two twizzles. In

the diagram below, the blue twizzle has its arrows parallel in the

way we've met before. It represents the number 1. The green twizzle

has its arrows at

and length 1 so that following the

number arrow would not move us along the number line at all but one

unit at right angles to it. The sum of the blue and green twizzles

(the grey twizzle) can be constructed using the rule for twizzle

addition. As shown, it turns out to have length

(using

Pythagoras) and be orientated at

to the unit arrows.

Figure 6

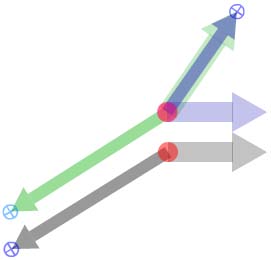

Now a multiplication. In Figure 7, the blue and green arrows

have been multiplied together as before, by matching the

lengths and directions of one unit arrow and one number arrow.

The grey twizzle gives the result: a unit arrow from the blue

twizzle and a number arrow from the green one. The size of the

grey twizzle (the length of its number arrow in units of its

unit arrow) is the product of the values of the green and blue

twizzles. The angle between its arrows is the angle of the blue

twizzle plus the angle of the green twizzle (measuring all

angles anti-clockwise from unit to number arrow).

Figure 7

Getting More Complex

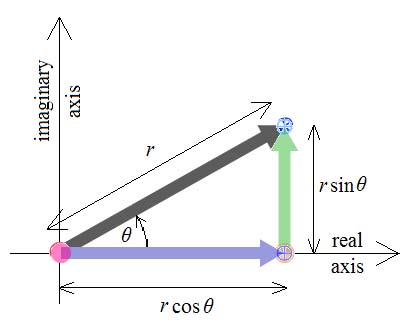

How should we describe the numbers whose twizzle arrows point

in different directions? Conventionally, we start by arranging them

on a diagram called an Argand diagram, like the one in Figure 8.

The tails of both twizzle arrows are placed at the origin, and the

twizzle is adjusted so that the head of the unit arrow is at one on

the horizontal axis. The head of the number arrow now indicates a

point which represents the twizzle on the diagram.Figure 8 shows

how the number

is represented.

Figure 8

Numbers on the number line have twizzles whose arrows both

point in the same direction, so these all sit on the horizontal

axis in the Argand diagram. These numbers are called real numbers

and the horizontal axis, which is really just the number line, and

is called the real axis. Numbers sitting on the vertical axis

aren't real, so instead of labelling it with the real numbers we

label it

,

,

, etc. where

, which stands for imaginary, tells

us that these numbers are on the vertical, imaginary axis instead

of the number line. So a point on the positive vertical axis one

unit from the origin represents a number called

whose twizzle is

two arrows of equal length pointing at

to each other, measuring

anti-clockwise from unit to number arrow.

What is the number

? We use twizzles to multiply

by itself.

The blue and green twizzles both represent

, and the grey twizzle

is their product.

Figure 9

So

, or in other words, i is a square root of -1. From our

experience of the real numbers, numbers have two square roots. So

what is the other root of -1? What other twizzle can be multiplied

by itself to give -1?

Figure 10

The numbers

and

are the square roots of

. And in the

same way,

and

are the roots of

,

and

are the roots

of

, and so on.

What complex number does

an arbitrary twizzle represent? Take a twizzle whose length is

times the length of its unit arrow, with an angle

between its arrows. We can construct any

twizzle from the sum of a purely real number,

, and a purely

imaginary one,

, as shown (Figure 11). The blue arrow has length

and the green arrow has length

. Basic

trigonometry gives the sizes of these real and imaginary numbers

and we can write our complex number,

, as:

Figure 11

A complex number can be described in two ways: by the

purely real and imaginary numbers

and

of which it is the sum,

or by its modulus (length),

, and argument (angle to the real

axis),

. It turns out that

is equal to

as long as

is in radians, not degrees. So another

way of writing the number represented by our arbitrary twizzle

would be

.

When adding and

subtracting complex numbers, the

form is helpful because we

can add or subtract the real parts of the two numbers separately

from the imaginary parts. For example,

|

|

This makes sense when we think of the twizzles on the Argand

diagram. The distance by which the "sum" twizzle moves us along an

axis is the sum of the distances each twizzle would move us on its

own.

For multiplying complex numbers, the

form is more helpful because we can

deal with the size and direction parts of the twizzles separately.

For example,

|

|

This makes sense

because, as we saw in Figure 7, the length of a product twizzle is

the product of the lengths of the factor twizzles and the angle is

the sum of the angles. To divide complex numbers, you would divide

the moduli and subtract the arguments.

Complex Numbers Reach Places other Numbers don't Reach

Think about the equation

.

Using the formula for solving quadratic equations gives us the

solutions

Before we knew about complex

numbers, we might have said that the equation had no roots, but now

we know that this is not true. It has no real roots, but it does

have two complex roots, at

and

. Complex numbers

have allowed us to answer a previously unanswerable question.

Now try

. The real numbers give us one solution:

.

But what if we use the

notation? The modulus of -1 is 1,

and we can say that the argument is

radians (

), but if the argument

were

,

,

and so on, the twizzle would still look the same.

Adding

radians to the argument of a complex number leaves it unchanged.

So, writing the equation again, expressing

as

,

|

|

and the solutions are

with

. Discarding the ones

which are the same as others by the "adding-

" rule

leaves three solutions:

|

|

The second of these is -1, which we already knew about, but the other two

are both complex. Once again, complex numbers have provided solutions we never knew existed.

We have just

uncovered a whole extra world of numbers. Might there be any more?

In fact, you can find all the roots of any polynomial equation

using just the complex numbers, a result known as the Fundamental

Theorem of Algebra.

Why Complex Numbers?

You can't have

apples in

a basket, or take

out of a cash machine, or

travel at

miles per hour, so why bother with complex

numbers? Are they just an intriguing mathematical phenomenon with

no practical meaning or use? The answer, of course, is no: complex

numbers are essential in Physics as the tools for describing

oscillating quantities: atoms vibrating in their molecules, the

swing of a pendulum or light waves travelling through space.

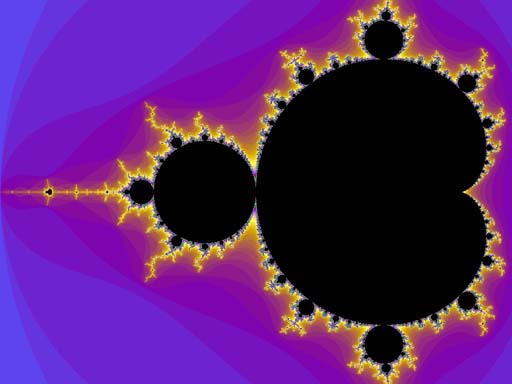

Complex numbers can also be used to think about geomety on a flat

piece of paper because they correspond to points on the Argand

diagram. A famous example is the Mandlebrot set (Figure 12). The

well-known image is in fact an Argand diagram, where the points

coloured black correspond to the complex numbers

for which the

series

doesn't tend to infinity.

Figure 12

Transformations of points are equivalent to

operations on complex numbers. For example, translating a point

units in the

-direction and

units in the

-direction means

adding

, and rotating

anticlockwise about the origin

corresponds to multiplying by

(to see this, think of doing the

arithmetic using twizzles). There are much more complicated

transformations, too, with all sorts of interesting properties, and

applications from drawing the field lines from an electric charge

to pinpointing the source of an earthquake based on measurements

made all round the globe.

Some Further Reading

For more information on topics skimmed over here, try these:

- For an intuitive proof of the fundamental theorem of

algebra without lots of mathematical jargon and notation, see

p38 of A Mathematical

Bridge by Stephen Hewson, published by World

Scientific.

- Plex

and Plex2

let you experiment with graphical representations of functions

of complex numbers.

- One of the geometrical transformations you can perform

using complex numbers, which is used for locating earthquakes,

is a stereographic projection. There's an animation, and some

description in words here .

- NRICH has two other articles on Complex numbers. What are

Complex Numbers? gives a sense of where complex numbers fit

into the bigger picture by bringing in related topics, such as

trigonometry, exponential functions and vectors. It also proves

that the exponential and trigonometric expressions for a

complex number are equivalent. An

Introduction to Complex Numbers goes into more mathematical

detail, and includes exercises.

- There's lots on the internet about the Mandlebrot set,

which you can easily find using Google. Wikipedia has

some particularly beautiful pictures. There's an applet for

exploring the Mandlebrot set here

, with a link to some explanation

.