How curved is a curve? How curved is a surface? When is a 'curved

surface' flat? We shall only briefly mention curves in the plane

and then move on to discuss positive and negative curvature of

surfaces.

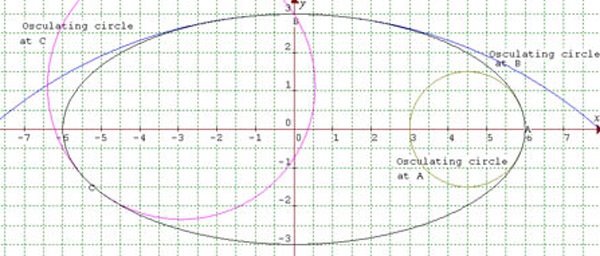

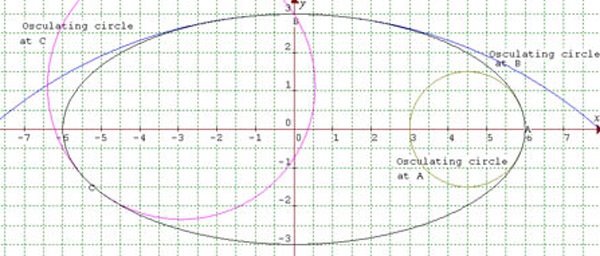

Imagine tracing out the ellipse shown in the diagram. How does

the curvature change as you go around the ellipse? Without

applying any mathematics everyone would agree that the tightest

bends are at the ends and the least curvature on the track around

the ellipse is halfway between these points .

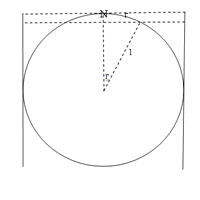

To measure the curvature at a point you have to find the circle

of best fit at that point. This is called the osculating

(kissing) circle. The curvature of the curve at that point is

defined to be the reciprocal of the radius of the osculating

circle. We shall not discuss in this article the method for

finding this radius accurately which needs calculus. Suffice it

to say that this circle has not only the same tangent at the

point (the first derivatives being the same) but also the curve

and the osculating circle have the same second derivatives at the

point.

Why use the reciprocal in defining curvature? It is natural for

the curvature of a straight line to be zero. Imagine

straightening out a curve making it into a straight line. In the

limit the circle of best fit has infinite radius giving zero

curvature.

|

The diagram shows

osculating circles

to the ellipse at

points A, B and C.

At A the curvature

is

,

at B it is

and at C it is

.

|

The following equations are given in case you want to plot the graphs

yourself, but ignore them if not and read on.

The equation of this ellipse is

At the point on the ellipse

with

, the curvature is given by

|

|

|

|

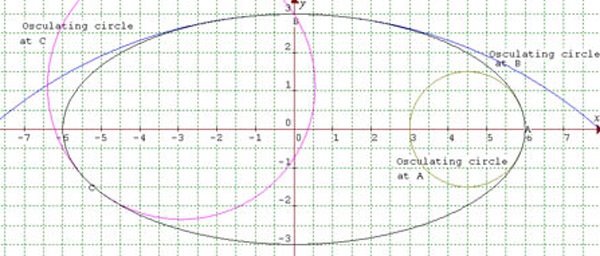

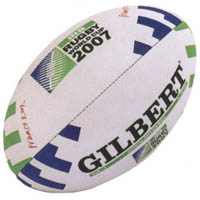

A perfect sphere has constant curvature everywhere on

the surface whereas the curvature on other surfaces is

variable. For example on a rubgy ball the curvature is

greatest at the ends and least in the middle. Measuring

curvature at a point using curves through that point on

the surface will not work. Which plane curve should we

use? At the '2' on the rugby ball, the curve in one

direction, going between the B and the E, has greater

curvature than the curve along the length of the ball.

Gauss proved that, taking the curvatures in all

directions at a point on a surface, the product of the

maximum and minimum curvatures at the point is constant

when the surface is distorted provided that lengths in

the surface are unchanged.

|

One method used to measure the Gaussian curvature of a surface at a point

is to take a small circle of radius

on the surface with centre at that

point and to calculate the circumference or area of the circle. If the

circumference is

and the area is

the surface is flat and is

said to have zero curvature. If the circumference is less than

and the

area is less than

the surface has positive curvature;

if the circumference is greater than

and the area is greater than

the surface has negative curvature.

There are three distinct geometries for the three types of surfaces and each

of these geometries has its own trigonometry with the results in each

trigonometry having counterparts in the other two trigonometries. Euclidean

geometry is the geometry of surfaces with zero curvature. Spherical geometry,

also known as elliptic geometry, is the geometry of surfaces with positive

curvature. Hyperbolic geometry is the geometry of surfaces with negative

curvature. See the article

How Many Geometries Are There?

.

|

What about the curvature of the surface of a cylinder.

Clearly the top and bottom are flat but what about the

surface, often called the curved surface, where the label

is wrapped around as in the illustration? Along the length

of the cylinder the curvature is zero and in other directions

there is positive curvature so the product of the maximum

and minimum curvatures is zero making the Gaussian

curvature zero. To see this another way, unwrap the label

and you can flatten it out,

draw a small circle of radius

anywhere on the label

and it has a circumference of

and an area of

Wrap the label around

the can again and the circumference and area of the circle

you have drawn do not change as the paper takes the shape

of the surface of the cylinder. So the surface of the

cylinder has zero Gaussian curvature.

|

|

In order to find the areas of circles on spheres we

shall use a result discovered by Archimedes of Syracuse

who invented calculus type methods almost two thousand

years before Newton and Leibniz. Archimedes made many

discoveries and inventions including the Archimedean

Screw pump, still in use today, depicted on this stamp,

and you can find out more about him on the

St Andrew's website. The result we shall use is

depicted in the diagram on the right and said to have

been on Archimede's tombstone.

|

|

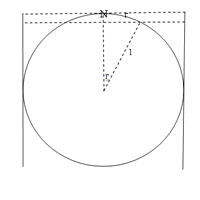

The cylinder shown has radius

, height

and area

,

the same as the surface area of the

sphere inside. Moreover the area of a

strip on the surface of a sphere cut off

by two parallel planes is equal to the area

cut off by the planes on the circumscribing

cylinder.

In this cross section, A and B

are planes at a small distance

dy apart, cutting the sphere and

circumscribing cylinder. The

'triangle' with sides dy, dx and dc

is so small that we can treat the

arc dc as if it were a straight

line and the hypotenuse of this

triangle. This tiny triangle is

similar to the triangle shown

with sides

and

so that

The area of the strip cut off by

planes A and B on the surface of

the sphere is

because

this strip has circumference

and height dc.

The area of the band on

the cylinder is

.

As we have shown that

it follows that these areas are

equal.

|

|

|

Now we study the curvature of the surface of a

sphere of unit radius. Take any point N and draw a

circle centre N radius

on the surface of the sphere

where the radius is an arc in the surface of the sphere

subtending an angle of

radians at the centre of the

sphere.

The circumference of the circle centre N radius

is

. Because

for all

non-zero values of

we see that this circumference

is less that

showing that the surface has positive curvature..

By Archimedes' method the area of this circle is

You can verify that this is

less than

, and hence that the curvature

of the surface of the sphere is positive, by drawing the

graphs of

and

on

the same axes and showing that

|

It is harder to model surfaces of negative curvature like a

saddle between two hills, the surfaces of cooling towers,

banana skins etc.A banana has positive curvature on the outside

of the 'bend' of the banana and negative curvature on the

inside.

Imagine you are at the lowest point on the saddle between the

two hills shown in the picture below.

|

Tie a long rope to a post at this point and, keeping

the rope taught, walk around a circle with the post as

centre. As you have to walk uphill and downhill as well

as around the post you walk farther than you would walk

on flat ground showing that the curvature at that point

is negative.

|

|

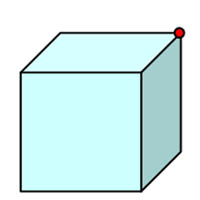

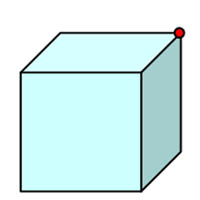

Gaussian curvature is closely linked to the angle deficiency of

the surface at that point. If the surface is flat and you draw

a circle centred at that point you go around 360 degrees.

At the red spot on the cube the angle deficiency

is

, the circumference of a

circle of radius

with centre at the red spot

on the cube is

so the curvature at that point is positive. The

curvature is concentrated at the vertices of

the cube rather than being distributed over

the surface as with a sphere or a rugby ball

shaped solid.

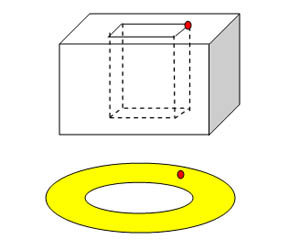

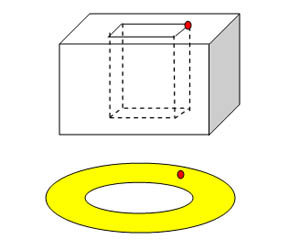

Although the curvature is concentrated at 16

points, the block shown with a hole through it

is analagous to the torus (or doughnut

shaped solid) shown in yellow.

|

We investigate the curvature at the red spot

at the edge of the hole in the block. The angle

deficiency at the red spot is

.

The circumference of a circle of

radius

with centre at the red spot

on the block is

so the curvature at that point is negative.

|

|

You can check for yourself the property (equivalent to Euler's

formula) that the total angle deficiency for any polyhedron is

720 degrees. The total angle deficiency for a solid depends on

the number of holes in the solid. For solids with one hole the

total angle deficiency is zero.

To read more on the subject of Gaussian curvature without getting

deep into higher mathematics see

this article and related articles from a workshp on 'Geometry

and The Imagination' led by John Conway, Peter Doyle, Jane Gilman

and Bill Thurston.