When you are working your way, with the youngsters, through a

long investigation it can be extremely useful to see how certain

people work - their route - if you like. I've found that one very

healthy route has been something like this, for example, when

working on

The Big Cheese:

1/ Start with practical - get results from the first block.

2/ Explore other blocks and then realise you are covering very

similar, if not the same, results.

3/ Ask questions like:

what about the surface area of the slices?

what about the surface area of the remaining block after each

cut?

what about the sizes of all the eventual slices?

4/ Tabulate the results - from simply writing them down in a line

to sophisticated spreadsheets.

5/ Explore the things in the table. This is where you are really

having a new branch of the investigation by exploring a set of

numbers from the table in their own right - probably forgetting

where they've come from.

For example,

You may look at the sizes of all the slices that came from the 5

by 5 block:

1, 1, 2, 4, 4, 6, 9, 9, 12, 16, 16, 20, 25

Perhaps you notice the square numbers that are here. They come

together in twos. When you add them to the adjacent non-square

number you get a triangular number. In truly investigative

mode, we ask WHY?

This is where we should try moving from this set of numbers we

found in the table back to the practical - looking at whereh

these numbers came from and getting diagrams to help.

So we move from the arithmetic exploration to playing around

with the practical again.

I shall show the practical in diagrammatic form.

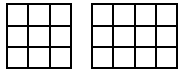

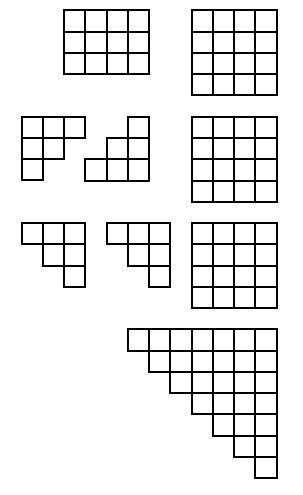

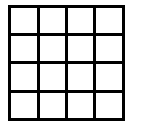

Here we have the 9 and the 12 slices.

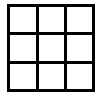

Now the 12 can be split:

These two triangular pieces could move onto the 3 by 3 square.

So the 9 and the 12 happily went together to form 21 - a

triangular number!

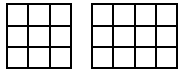

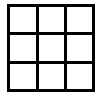

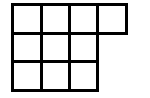

Now let's try the same with the 12 and the 16. Here are the

four stages.

So practically we can appreciate the joining of each square

number with the adjacent non-square number to form a triangular

number.

Appreciating this practically helps many pupils to gain a better

realisation of the relationship between these two sets of

numbers.

Having come away from the table of results and explored some

relationships practically we could end there, BUT if the group

have an opportunity to go back then, with greater confidence now,

they can ask further questions. I would recommend that you invite

the youngsters to ask the kind of questions that would lead to

more exploration, more calculations AND maybe back to the

practical again. An example might be;

"What's the suface area when we start with a 5 by 5 by 5 cube?"

[150]

"After the first slice [a 5 by 5 by 1] is taken, what's the total

surface area of the two pieces?"

[Well the starting cube is now only 5 by 5 by 4 and so has a

surface area of 130 and the slice is 5 by 5 by 1 and so has a

surface area of 70, giving a total of 200! . . . . . .]

Sometimes when doing investigations we are very practical and

find all we need to without having to go into complicated

arithmetic. BUT what happens when trying the "

Brush Loads

" investigation?

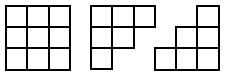

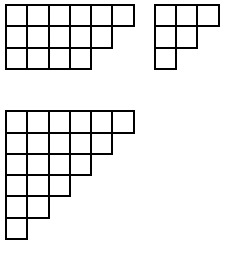

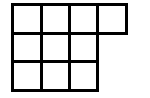

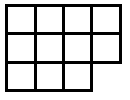

Suppose you go along the route of finding the smallest surface

areas for different numbers of cubes. The discovery is usually

made - see activity notes - that the shapes have to be flat. So

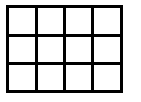

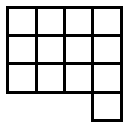

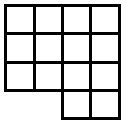

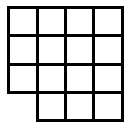

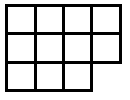

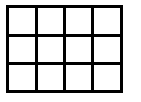

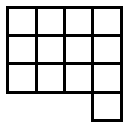

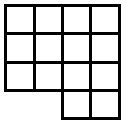

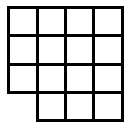

let's look at some of the answers shown in plan view:

Now, as mentioned in the notes for this activity, children count

the squares on the surface in different ways. Those who settle

for viewing from the four sides and then adding the top sometimes

have found out that they only have to consider, in these

examples, two adjacent sides.

The two adjacent sides are viewed and then added and doubled.

Finally the number on the top - the number of cubes - is added

on.

Looking at the examples above we have:

9 cubes give 3 + 3 doubled + 9 = 12 + 9 = 21

10 cubes give 3 + 4 doubled + 10 = 14 + 10 = 24

11 cubes give 3 + 4 doubled + 11 = 14 + 11 = 25

12 cubes give 3 + 4 doubled + 12 = 14 + 12 = 26

13 cubes give 4 + 4 doubled + 13 = 16 + 13 = 29

14 cubes give 4 + 4 doubled + 14 = 16 + 14 = 30

15 cubes give 4 + 4 doubled + 15 = 16 + 15 = 31

16 cubes give 4 + 4 doubled + 16 = 16 + 16 = 32

Now the patterns and arithmetic can be explored further

according the the abilities of the youngsters involved. I could

imagine some pupils being able to talk about a sort of formula

that would be a kind of generalisation.

So let's be clear that when working practically we may need to

explore what's going on arithmetically and when working

arithmetically we may need to explore what's going on

practially.