The NRICH problems are organised into

Stages (Tin Tight is a Stage 4 problem), and the solutions

selected are those that use the repertoire of mathematical

knowledge at that level.

Tin Tight would be a straightforward problem at Stage 5 where a

technique from a topic called Calculus would produce a routine

solution very easily.

At Stage 4 a Trial & Improvement approach would work well,

using either a calculator or a spreadsheet.

Alternatively software or calculators that plot graphs from

algebraic functions will produce an interesting visual

representation of the same approach.

Well done to Zoë from Bournemouth and to James and

Mary from Edinburgh. Here's how they tackled the problem

First of all we imagined some extreme tin proportions.

If the height was really small, say 1cm, then the tin would

have to be enormously wide to still hold a litre, and that means

having a big lid and bottom area.

If, on the other hand, the height got very large the tin would

be like a tube.

We weren't sure straight away whether that made the all round

area bigger or smaller. So we tried some calculations and it

looked like the area got bigger for taller (thinner) tins.

If the height was

the base area had to be

because we know that

the volume's going to be

. Then the base is a circle so an area of

means a radius of

which is a diameter of

.

The curved part of the tin is a wrapped round rectangle. And tin height

and base circumference gives us the dimensions to calculate that area.

Then we just add the base and the lid, which is the same as the base,

and that gave a total area of about

.

Next we tried a height of

. That tin had a total area of about

. Heights of

,

and

had areas of

,

and

. So you can see that it looks like taller tins use

more material to make them.

Now to find the best value. That is the height of the tin that

needs as little material as possible and still holds 1 litre.

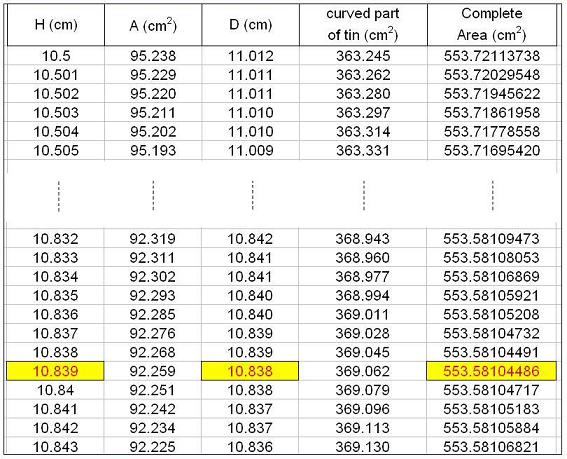

Rather than keep using the calculator we decided to use Excel,

because it was the same calculation over and over but just with

height changed by a steady amount each time.

Here's what we got (A is the base area which is a circle, and

D is the diameter of that circle. The formulae in the cells just

do the calculations we already explained)

That is just part of the sheet. Our H numbers actually went up

as far as 100.

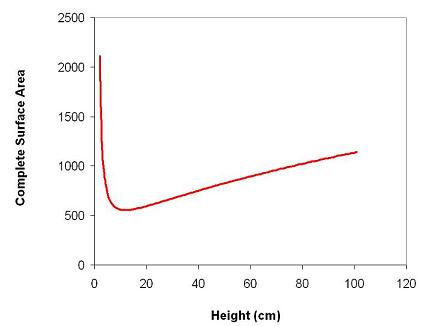

We also made Excel show the results as a graph, which made us

more sure that the best height was well before 20 cm

Next we reduced the increase amount for H to get a more accurate

result.

We already knew that the answer would be near 11

It seems like we need a height of about 10.84 cm and that gives a

diameter which is the same as the height. We did try using more

and more decimal places just to make sure.

Our conclusion is that it looks very much like having the height

and diameter both the same will make the most efficient tin.

Which is a bit surprising and rather nice!

Although, except by doing the calculation, we can't see why it

should be that proportion.

What about 5 litres?

We could invent a new unit of capacity that was equal to 5

litres. Then all our calculations and reasoning would remain the

same. The best proportion would still be when the diameter and

height were equal. So this is the best proportion for any size

tin.

For those who like to look ahead Alison from

Guildford shows how quick the result can be using Stage 5

mathematics :

For a cylinder, volume (V) is

.

And the total surface area (A) is

.

But if V is specified, h will depend on r.

The formula is

.

And using that to replace

in theformula for total surface area:

.

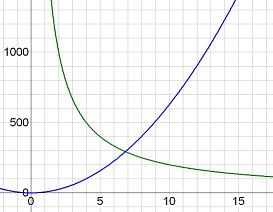

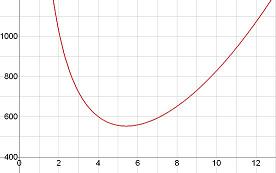

Sketching the area function (A) is straightforward.

(blue) and

(green) are simple curves, so the Area Function

looks like this.

From this we can see that there is only one r value to consider

and that that position is a minimum.

Differentiate the Area Function to get its Gradient Function:

(that was the Calculus bit!)

And this function is zero when r is 5.419261

So the minimum surface area for the cylinder happens when r is

5.419261, that is a diameter of 10.83852 and when the height is

also 10.83852 using the formula (above) for h when r is known