Simplifying Doughnut

Can you match up these equivalent algebraic expressions?

Problem

This activity is designed to be tackled in pairs or small groups, but can also be completed individually. For more information on how this can be done in groups, take a look at the teachers' resources.

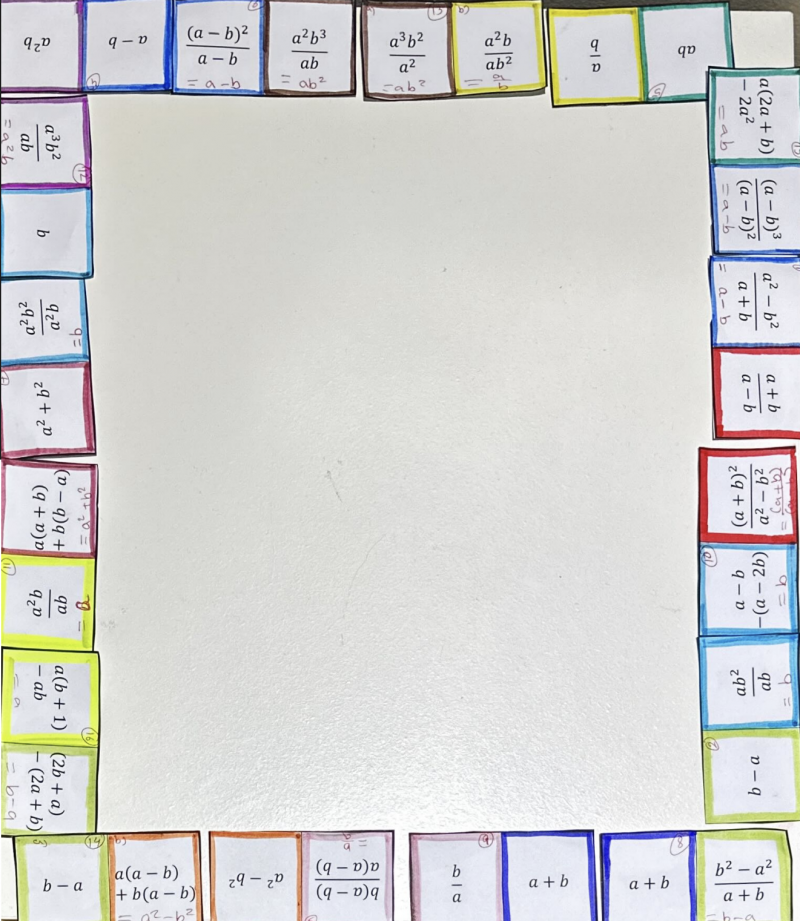

These printable domino cards can be put together to make four 'doughnuts' of four dominoes. The ends of dominoes which join together need to be algebraically equivalent.

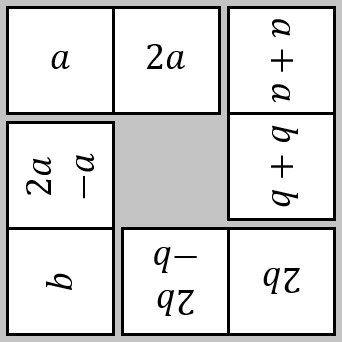

For example, a doughnut could look like this:

Have a go at making the four doughnuts. What do you notice?

Once you've made four doughnuts, you might like to try using the same set of cards to make two large doughnuts instead, with eight dominoes in each doughnut.

Is it possible to make one very large doughnut, using all sixteen cards? And if it is possible, is there more than one way of doing this? How many can you find?

Student Solutions

It looks like there's only one way to make the four small 'doughnuts', counting rotations and reflections as the same solution, but there are more ways to make the larger doughnuts.

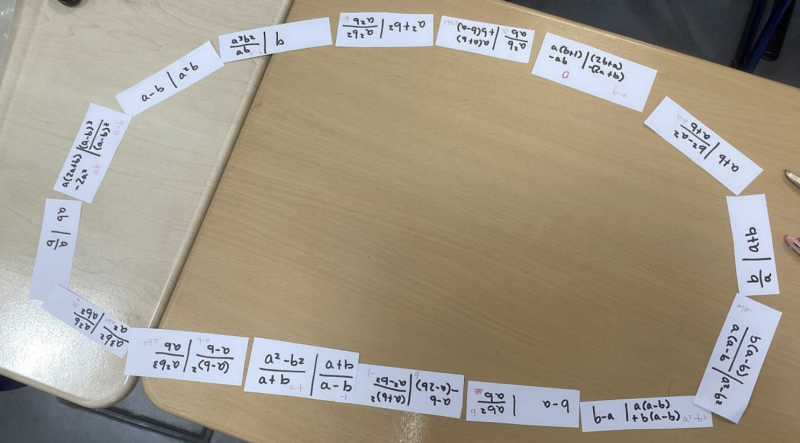

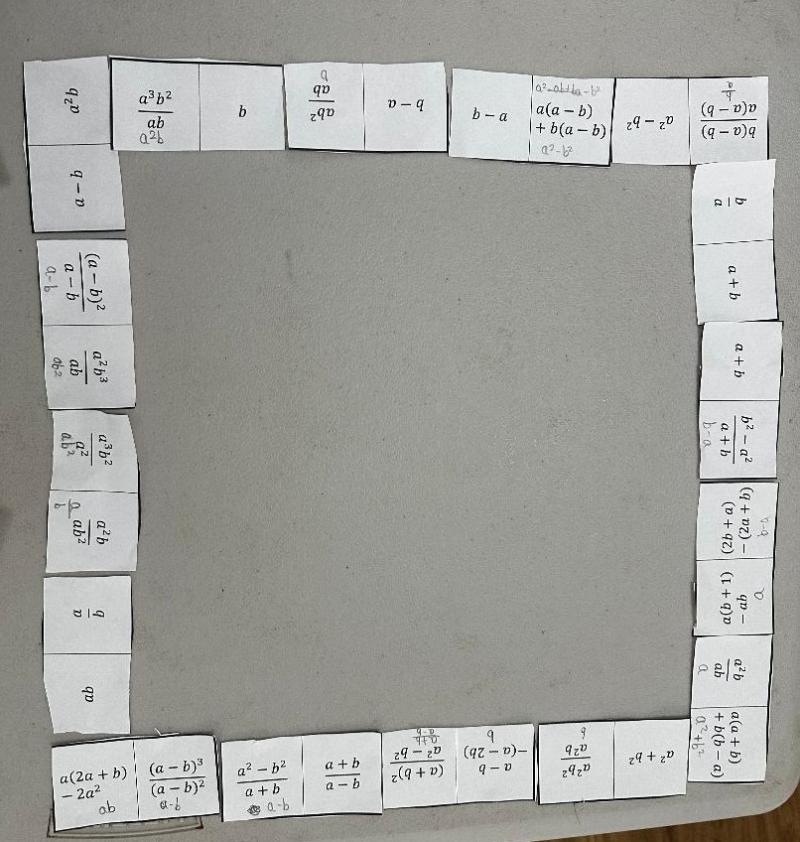

All of the images on this page can be clicked on to enlarge them.

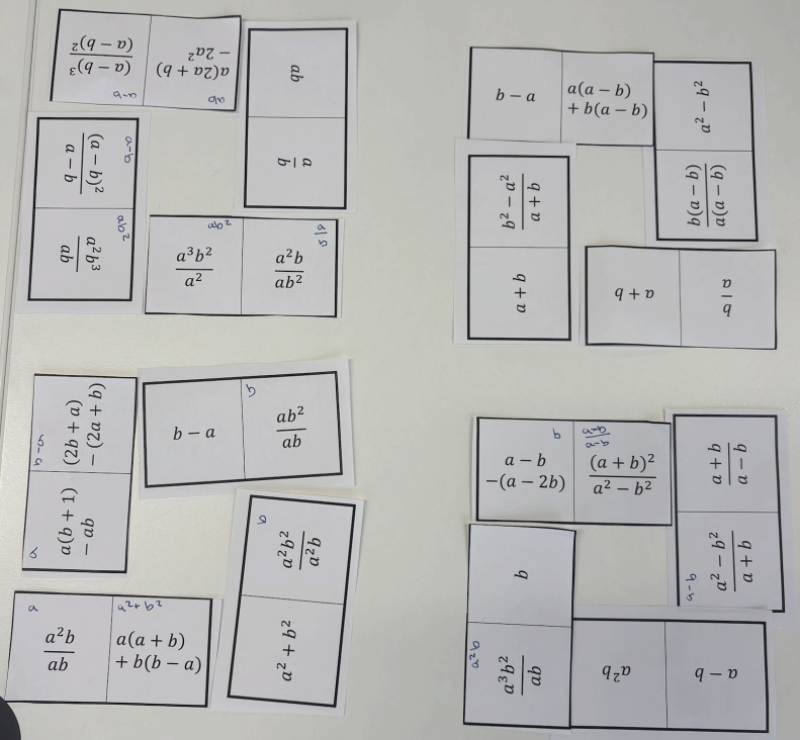

Meja and Nathalie from ISZL in Switzerland started by using trial and error to match up the dominoes:

Our initial approach to this problem was using the trial-and-error method. We had previously cut all of the squares out and were trying to match up the first pairs we could see. After a while, we realised that most of the problems could not just be seen initially, and needed some working out to be able to be paired up. This was when we decided to start simplifying the problems that were not already in their simplest forms, and thereafter wrote them on their designated card. This allowed us to, in a much quicker and easier way, match the cards up with a designated pair. After all of the cards had a pair, we started connecting the pairs to another, which quite quickly allowed us to form all four of the donuts.

Harnoor from Doha College in Qatar also simplified the expressions on the cards, and then used colour to keep track of equivalent terms:

First of all, I went through all the domino cards and found that a lot of them could be simplified. This would make it easier for me to to sort them out.

I then simplified the expressions on all the domino cards to their simplest forms (you can see these in Harnoor's PDF solution).

I then started to create the doughnuts by attaching the same terms, however, it was really puzzling to have a look at all these terms all together. To resolve this, I color coded the same terms with similar colors so that it becomes visually easy to sort.

Once this was done, it was super easy to create four doughnuts by attaching the same colour ends clockwise after trying a few combinations. Creating two large doughnuts was also not very difficult.

After creating two doughnuts I went ahead to create a big doughnut using the same process I had used to make the previous two. Unlike the other two making the big doughnut took some time but after some trial and error I finally made it. There should be more possible ways of doing this because there are multiple dominoes with similar terms. Ex: (a-b), (b-a), b occur 4 times.

Harnoor is right - because there are more than two dominoes which feature a-b, b-a and b, there are multiple ways of matching these dominoes to make the large doughnut. I wonder how many ways there are?

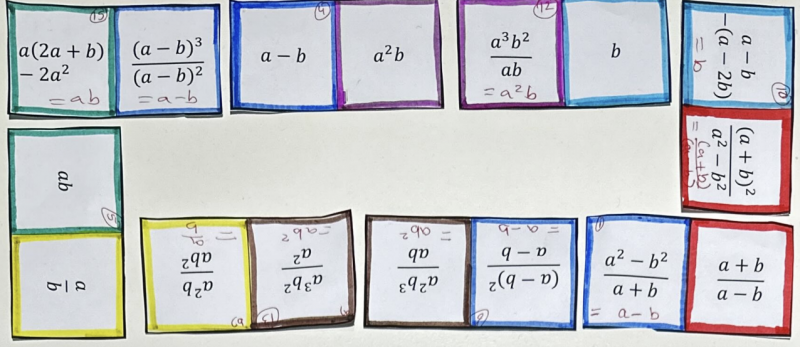

Yasmin from Doha College in Qatar found a different way of making the large doughnut:

Akhil from Cannon Lane Primary School in the UK found a slightly different solution:

To start with, I simplified expressions on all dominoes to their simplest form and wrote down the simplified form underneath the expression on the domino. Then I solved using the same technique as in one of the earlier questions - get started with one domino and find two matching dominoes for that domino and so on until the complete doughnut was complete.

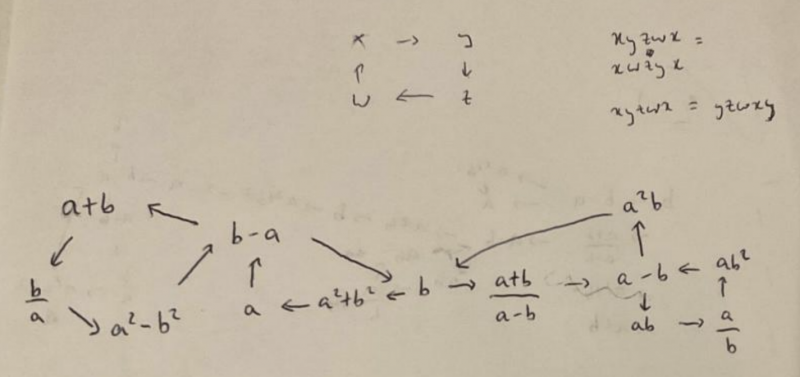

Yatharth from WBGS in the UK decided to draw a map to work out the number of possible 16 link doughnuts:

Yatharth explained:

Let's say we start at $b$, notice we have 2 choices, go left or right.

If we go right we have 2 more, go to $a^2 b$ or to $a+b/a-b$

2 more when we approach the loop at $a - b$, we can traverse the ring clockwise or counter-clockwise.

Due to the choices we made, we can only go to $b$ through one route.

We have 2 more choices, to go to $b - a$ or to $a$.

We have 2 more choices, to traverse the ring at $b - a$ clockwise or counter-clockwise.

We now have $2^5$ options for $b$ to $b$ which is 32. We now also have 32 for the other degree 4 nodes. Despite this we only count one set as each completed route can be written from different starting points. Ultimately, you are still traversing the same path by rotational equivalence (xyzwx = yzwxy)

For example, take L1 to be any form of route through the left cyclic loop and R1 to be any route through the right cyclic loop.

In the 32 we will have L1+R1 and R1+L1 which are just equivalent as they are the same map but in a different order. Therefore, we divide by 2 to obtain 16 choices because of duplicates.

Now in the 16, we also have 8 perfectly opposite pairs. In the rules we laid out we said xyzwx = xwzyx, showing that clockwise and counter-clockwise traversals are just opposites of each other and are equal by directional equivalence.

Take L1+R1 to be our route, in the 16 we will also count reverse (L1+R1). These are just the same as we traverse the map in different directions. As a result we have 8 unique choices and 8 reversed forms.

Overall, we have 8 different 16 link doughnuts we can make.

This is very carefully reasoned - I like the way that the map makes it clear that there are four sections, and we can begin to think about how many ways of moving through each of the sections there are. Take a look at Yatharth's full solution to see more of their ideas.

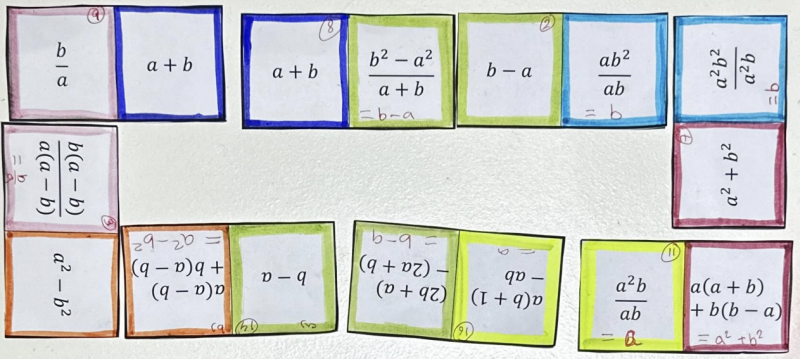

Neel and Noah from Heckmondwike Grammar School in the UK also thought about the dominoes as edges and vertices of a graph, and they wrote a computer program to find the number of possible 16 link doughnuts:

We started off by simplifying all the algebraic expressions into forms with just A, B and normal operations. Then we manually arranged the cards by finding certain restrictions. We then noticed that the dominoes could be intuitively though of as edges and vertices in a graph with the expressions being vertices and edges being the connections in the doughnut. We then noticed that a doughnut is a bunch of edges (4, 8 or 16) that can be traversed without overlap. From this we can find all the doughnuts by finding all the cycles in a directed graph of dominoes of a certain length (4, 8 or 16). We used depth-first search for this (a graph exploration algorithm) to ensure we found all the possible solutions without duplicates. To do this we terminated checking a branch early if it failed the criteria of connecting to form a doughnut. We prevented counting of duplicates by not repeatedly counting rotations or reflections of existing solutions (finding only canonical cycles). Since there are only 16 edges, the sample space is small so we can search all solutions in quite fast times. We have included our written python code which outputs all the solutions, along with our first manual arrangement and a further intuition overview in the attached file.

Take a look at Neel and Noah's full solution to see the code they used for their calculations. Like Yatharth's method, their code also finds eight possible 16 link doughnuts.

We also received similar solutions from: Joy; Ziqian from Harrow International School in Hong Kong; Nikhil from Doha College in Qatar; Rebekah and Nilasi from ISZL in Switzerland; Peter from St Paul's Primary School in the UK; Dhruv from The Glasgow Academy in the UK; and Vivaan from JBCN International School in India. Thank you all for sharing your thinking with us.

Teachers' Resources

Why do this problem?

This problem provides an opportunity for students to work together collaboratively to simplify algebraic expressions in an engaging context.

Possible approach

This activity can be done in a very structured way in groups of four (or five, including an observer). The cards can be handed out randomly - four dominoes to each group member - and the group can work together in silence, with learners handing one of their cards to another learner based on their observations of each other's needs. An observer can make sure the team obeys the rules, as well as making a note of times that members of the team responded to the needs of others.

Observers can also give a hint if no progress is being made. This hint should be to point to one of the expressions and to say something along the lines of, "Think about how many dominoes have an end that is equivalent to this expression."

As teams finish, ask them to discuss what they have learnt about working together. Use observers to feed into the discussions. Then spend some time discussing as a class how they might work more effectively in future.

Key questions

As this task is designed to be carried out in silence, the use of key questions is inappropriate during the task but can inform discussion of team behaviours when the task is complete.

- Can you give any good examples of when someone noticed what you needed and tried to help?

Possible support

Some learners might find it easier to work in a less structured way with these dominoes. For example, being able to move the dominoes all freely around and being encouraged to write on the dominoes to keep track of the equivalent algebraic expressions will make this task more accessible for some students.

Possible extension

The dominoes can also be arranged into some larger doughnuts. Ask the team to create these shapes.

Learners could also work on making their own algebraic dominoes. What makes a good set of dominoes for this activity? What would they change/keep the same about the features of the set of dominoes in the problem?